The Hundred Set Solution: A Young Innovator Reimagining Yam Farming in Ghana

In Afram Plains, a rural area in Ghana, Nadia Modoc, an agricultural strategist, is confronting a gap head-on. Drawing on regenerative agriculture and systems engineering principles, Nadia has developed a greenhouse-based yam propagation model that multiplies seed sets exponentially, transforming one vine into as many as eighty viable planting units in half the time of conventional methods.

Her approach is born out of an intentional design, reflecting a bold synthesis of scientific reasoning, ecological awareness, and grassroots development. Yam farming in West Africa is often portrayed as a laborious and low-yield practice embedded in rural tradition. Yet beneath this perception lies a missed opportunity, and an under-explored intersection of biotechnology, agrarian innovation, and indigenous knowledge systems.

Nadia Modoc is a digital transformation strategist and agro-innovator pioneering a climate-smart solution to yam farming through greenhouse-based seed multiplication. With a background in technology and grassroots development, she leads a family-run project in the Afram Plains that transforms single yam vines into over 80 viable seed sets. Nadia’s work preserves indigenous crop varieties, empowers local farmers especially women and redefines agriculture as a space for innovation, ecological resilience, and community transformation.

A New Agrarian Consciousness

Ghana continues to experience a dreadful drift of rural youth migrating to urban centers, lured by the illusion of modernity, while agriculture is framed as a relic of poverty. The cost of this movement is a gradual erosion of ecological knowledge and a surge in unemployment. In the face of this crisis, Nadia’s work takes on revolutionary significance. Her yam multiplication model enhances productivity and challenges the epistemic frameworks around what constitutes viable, modern agriculture in West Africa.

With a professional background in the technology industry, her decision to engage in yam farming emerged as a strategic intervention sustained by observation and a response to developmental gaps, she encountered during her formative years spent between urban life and visits to farming communities in the Afram Plains. Unlike many of her peers who view agriculture as either a last resort or a legacy profession, Nadia saw it as an open canvas for innovation.

“For me, I wanted to make farming easy for the people living in the community,” Nadia explains.

Her familial environment played a pivotal role in this awakening. Growing up with a father deeply embedded in non-governmental organization-led agricultural work, she became sensitized early to the constraints and inefficiencies local farmers face, particularly concerning access to quality inputs, unpredictable weather cycles, financial constraints, and the erosion of indigenous farming knowledge.

“They would ask me, ‘Daddy, what can we do to support these farmers?’” her father, Kwaku Modoc, recalls.

Today, farming for Nadia and her family is not merely subsistence or tradition. It is a multigenerational enterprise that fuses technology, experimentation, and social transformation.

“We are not doing regular farming. We are doing something different. Something that allows agriculture to scale,” she explains.

In that statement lies a core philosophy that modern agriculture must be treated as a platform for design thinking, one that integrates scientific processes and community impact.

The Science of Multiplication: Rethinking the Yam Lifecycle

At the core of Nadia’s project is a brilliant innovation that reimagines yam propagation through a greenhouse-based system emphasizing vegetative node multiplication. Conventional yam farming in Ghana typically involves the direct planting of whole yam heads or large segments, a practice that demands significant land, time, and resources while yielding modest outputs. In contrast, Nadia’s method treats the yam vine, as the primary reproductive material.

This shift, though seemingly minor, has major implications. Each vine node, the joint between leaf and stem, becomes a potential plant. When treated in nutrient-enriched soil, often fortified with neem tree leaves for natural pest control and microbial balance, these nodes can each produce two viable mini sets. A single vine can generate up to fifty nodes, each with the capacity to duplicate itself, ultimately producing high-quality yam sets at exponential rates.

The system follows a tripartite cultivation cycle. First, vine nodes are planted to generate micro mini sets within three months. These are then re-cultivated to become mini sets over another three-month period. Finally, the mini sets are grown into full yam sets in approximately five additional months. From propagation to maturity, the entire cycle spans roughly eleven months, but by the sixth month, farmers already possess viable planting material, halving the gestation period required by traditional techniques.

“Compare that to the traditional method which takes a whole year, and even then, one yam gives you one seed. Here, one plant can give you up to 80 mini sets,” her father explains.

In the compact space of their greenhouse, the team has managed to cultivate a number of mini sets as pilot. This is an increase in volume, and a paradigm shift in how planting materials are sourced, scaled, and distributed.

More significantly, this innovation decentralizes yam production. It moves cultivation away from climate-vulnerabilities, and land-heavy systems toward smaller, controlled environments where resource efficiency can be tightly managed. Nadia is treating farming as an engineered ecosystem, not a brute-force act of labor.

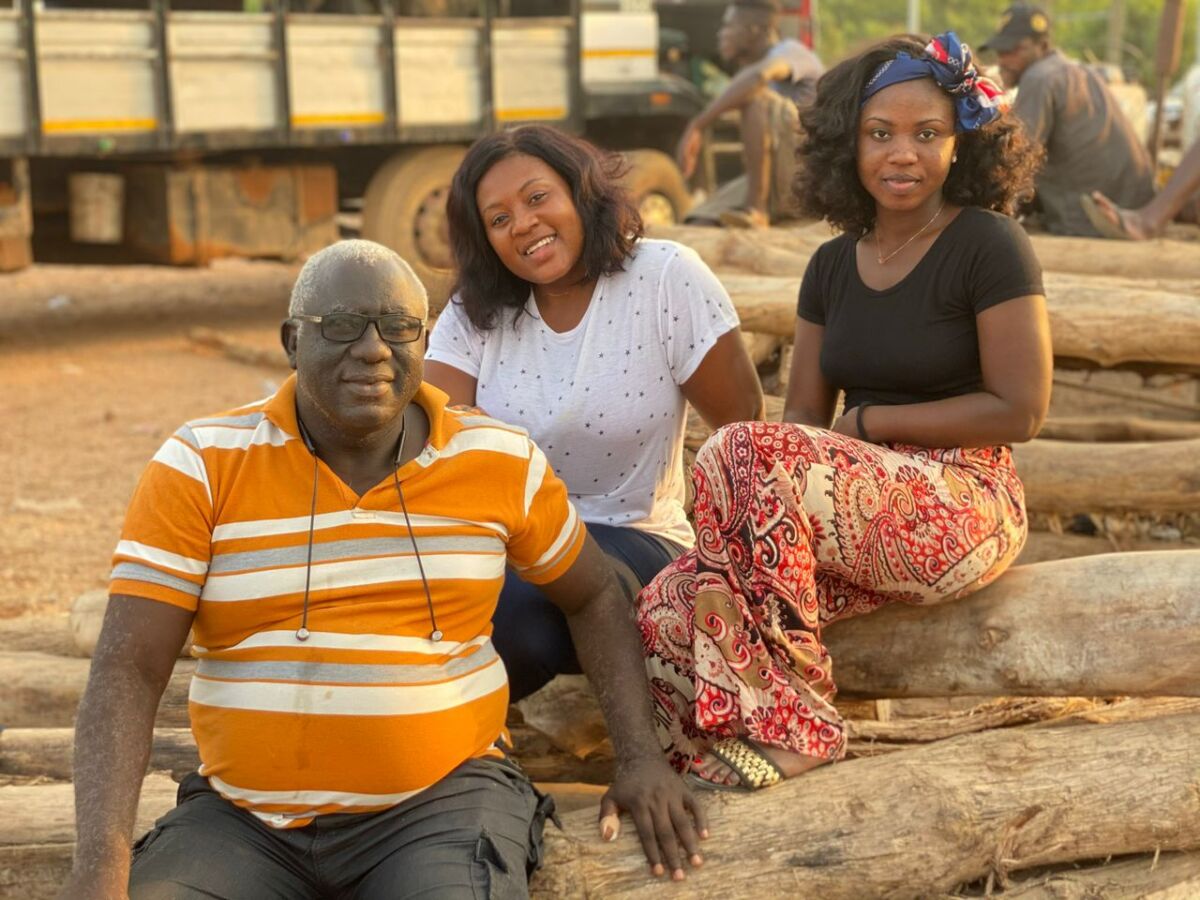

The Modoc family pioneering greenhouse-based yam seed multiplication in Ghana

Reviving Genetic Memory on Biodiversity and Cultural Loss

Beyond the quantitative gains lies a qualitative mission of preserving endangered yam varieties.

“We are losing our traditional yam species like Puna and Credo, which are indigenous varieties. Farmers don’t even get good seedlings to plant anymore” Nadia laments.

This dimension of the project reframes the greenhouse as a genetic facility. By cultivating older, less commercially dominant species under controlled conditions, Nadia is safeguarding genetic diversity that would otherwise be lost to monoculture and climate degradation. The implications stretch beyond Afram Plains. The family is advocating for food sovereignty, cultural identity, and the intergenerational inheritance of biodiversity.

A Feminist Reclamation

In a space where young women are often disincentivized from entering agricultural domains, Nadia’s presence as a systems-builder challenges deeply rooted gender bias.

“Young people have vast lands they inherited from their parents, yet they still cry about unemployment. They want white-collar jobs, which should not be the case. As a young woman, I want to make them know that they can be farmers and still flourish,” Nadia cautions.

Her work confronts dual urban skepticism: that farming is an unambitious pursuit and that women lack the technical acumen to lead in agriculture.

“We want people to see that you can return home and still innovate. It’s not a step backward,” she affirms.

Through action, she is building a gender-inclusive narrative around farming, one that affirms intellect, experimentation, and strategic design as possibilities accessible to women.

Designing for Diffusion and Scalability

Nadia’s most distinguishing feature is the potential for replication and local ingenuity. The greenhouse is deliberately low-tech in structure, relying more on innovative knowledge systems and local infrastructure than external machinery.

The family has already begun piloting node-based propagation with crops such as millet, guinea corn, and soybeans to test the versatility of their node-based propagation system.

“We want to test everything. This is not just a module for yam farming, we are on a mission to proving that sustainable agriculture is possible at a community level,” her father says.

The question of partnerships now looms large. With the right institutional support, agricultural extension programs, and agroecological networks, this model could scale across regions facing similar constraints.

“Right now, we are just trying to get it right. But yes, with support, we can teach others, supply sets, and maybe even expand this across the region,” Nadia says.

Though she is still in the wee stages of her journey, Nadia and her family are methodically building a model that could serve as a national template. Already, they are comparing greenhouse and open-air results, refining soil treatments, and adjusting cycles based on local weather patterns.

Her dream is to see a Ghana where every farmer, regardless of location or background, has access to quality seeds and the knowledge to multiply their harvest efficiently.

Cultivating a Legacy: Toward a New Agrarian Ethos

Nadia’s initiative is a call to reimagine farming as a site of experimentation, dignity, and potential, not as a vestige of poverty or the past. For her and her family, farming is a multigenerational effort that bridges technology, tradition, and purpose. This greenhouse model is a paradigm shift. It transforms yam farming, once a linear, resource-heavy operation, into a dynamic, scalable, and resource-efficient system.

Instead of importing headsets at high costs or depending on failing rainy seasons, communities can create micro-factories that provide food security and financial resilience.

Leave a Reply