Storm Donald Rages: Global Cooperation Under Pressure

The international landscape is changing faster than ever. Budget cuts, national interests, and geopolitical shifts are pushing global cooperation and health programmes into uncertain waters. This first article in a series by Vice Versa explores the impact of these changes on development cooperation, local communities, and health systems worldwide. It also shows how new strategies and partnerships are emerging in the midst of this storm.

The year 2025 is one big tropical storm that refuses to subside. The name of the storm is Donald, and he is sweeping across the world at full force, ever since his inauguration on the 20th of January as the president of the United States. The course of the storm is likely even more erratic than the unpredictable weather patterns resulting from climate change.

Donald leaves traces everywhere. A trade war he has unleashed is causing major fluctuations in the stock markets and uncertainty among entrepreneurs and citizens active on the stock exchange. The United States is no longer a natural ally of Europe.

At home, Donald is undermining the very foundations of the rule of law, despite the United States’ long democratic tradition. He has mounted a sustained attack on the independence of the judiciary and the press, with judges and journalists routinely discredited. Critical universities are denied government funding, and students are arrested because they participate in protests against the war in Gaza.

Cuts to Development Cooperation

Donald’s actions also carry major consequences for global development cooperation. He has halted almost all critical USAID programmes. And he is not alone: the Netherlands (30 percent), the United Kingdom (40 percent), Germany (50 percent), France (25 percent), and Belgium (25 percent) are also slashing their development budgets. The way this is done varies from immediate and abrupt (as in the United States, where the courts are then consulted to determine whether the action can be halted) to gradual (as in the Netherlands, where existing programmes and commitments are respected).

What is also new is the narrative being used. Development cooperation is no longer about justice, human dignity, or keeping the world livable together, which requires sharing some of our prosperity. Instead, it is about self-interest. International cooperation has (once again) become transactional.

In June 2025, for example, the Trump administration brokered a peace agreement between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), aimed at ending years of border tensions in the Great Lakes region. Signed in Washington, D.C., the deal is widely hailed as a diplomatic achievement and a step toward stability in one of Africa’s most resource-rich regions.

Yet American involvement is far from altruistic. In exchange for its mediating role, the United States has secured access to strategic minerals and supply chains in the DRC—cobalt, copper, lithium—essential materials for the production of batteries, semiconductors, and other technologies that fuel the energy transition and the defence industry.

Aid must, above all, deliver returns. The Netherlands is no exception. In the very first sentence of the February 2025 policy brief Ontwikkelingshulp, Minister Klever writes: ‘This cabinet once again prioritises the interests of the Netherlands, including within the Foreign Trade and Development Aid portfolio. This aligns with the changing global power dynamics. We are going to do things differently.’

In an interview with De Telegraaf, the now former minister states: “Dutch entrepreneurs must bring in more money. One-third of our income is earned through trade abroad. We want to increase that by deploying development aid.”

Although Klever’s party, the PVV, left the government in June 2025, Dutch development policy is still based on her policy brief.

Halting USAID Projects

The cuts to development cooperation have far-reaching consequences. Above all, the near-complete shutdown of USAID leaves deep scars. It affects dozens of countries and millions of people at once. Programmes that for years formed the backbone of health care, food security, and education are abruptly halted. In African countries, this means HIV clinics close, malaria prevention programmes stall, and vaccination campaigns are cancelled. A study by the University of California estimates that this could result in more than fourteen million additional deaths by 2030, including over four million young children.

The indirect consequences are just as severe. Local health organisations lose not only funding, but also the expertise and coordination structures they relied on. Decades of building health systems crumble, leaving governments in vulnerable countries unable to absorb the sudden shortages. Where USAID once collaborated with local partners to prevent epidemics, there are now empty offices and unpaid nurses.

The cuts also undermine global health security. Less surveillance of infectious diseases means that outbreaks are detected later, and regional crises can quickly become global threats. What began as a political intervention in Washington may end as a health crisis in Kinshasa or Kampala.

For countries that have relied on American support for decades, the message is clear: solidarity is no longer self-evident. Health, just like peace and trade, has become a matter of power and interests.

Responses to the Cuts

Across the world, there is astonishment at the dismantling of USAID, which accounts for 40% of global aid. “This is a frontal attack on human dignity that will cause immeasurable suffering,” says Alistair Dutton, secretary-general of Caritas International.

But after the initial shock, a different kind of bewilderment emerged in many African countries. Isn’t it absurd, people asked, that we are still so dependent on Western development aid? How is this possible? And, how can we change it?

According to Cameroonian economist Célestine Monga, development aid has often bound Africa more than it has liberated it. “Anyone who takes themselves seriously would not beg for small amounts for sixty or seventy years,” he says in an interview with NRC. If Africa wants to determine its own course, the first step, he argues, is not more aid but emancipation from it. Strategic investments in industrialisation, infrastructure, and local entrepreneurship should enable African countries to take control of their own development. The shock of so much aid being cut could finally set this in motion.

Others point out that the cuts may lead citizens in low- and middle-income countries to hold their own governments more accountable for the governance of their country, to exert more pressure on corruption and political decisions that do not benefit the majority of the population. Young people may play an integral role in this, as shown by the mass Gen Z protests in Kenya last year and Tanzania this year.

Improvers versus Reimaginers

Within the Dutch development sector, an interesting debate is taking shape.

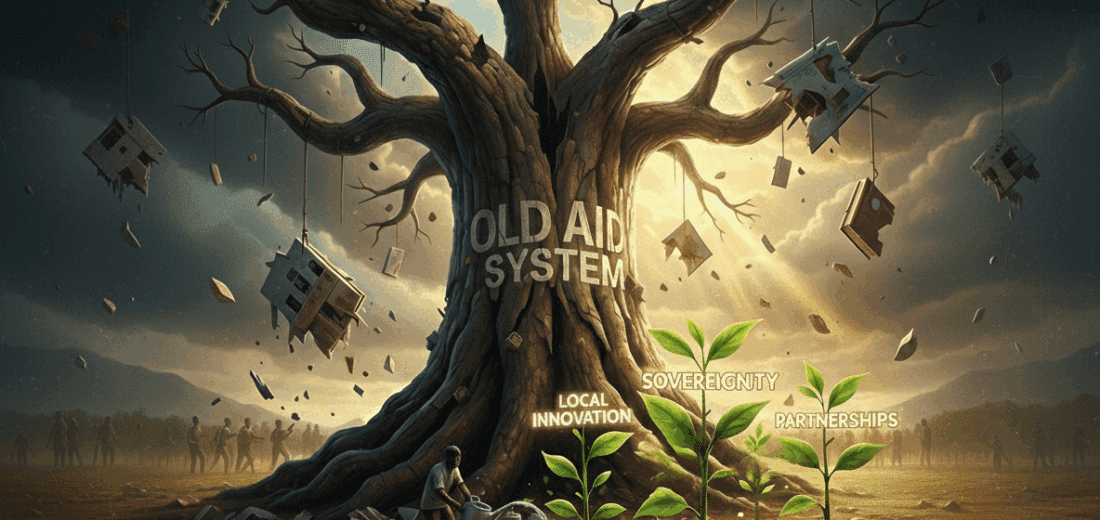

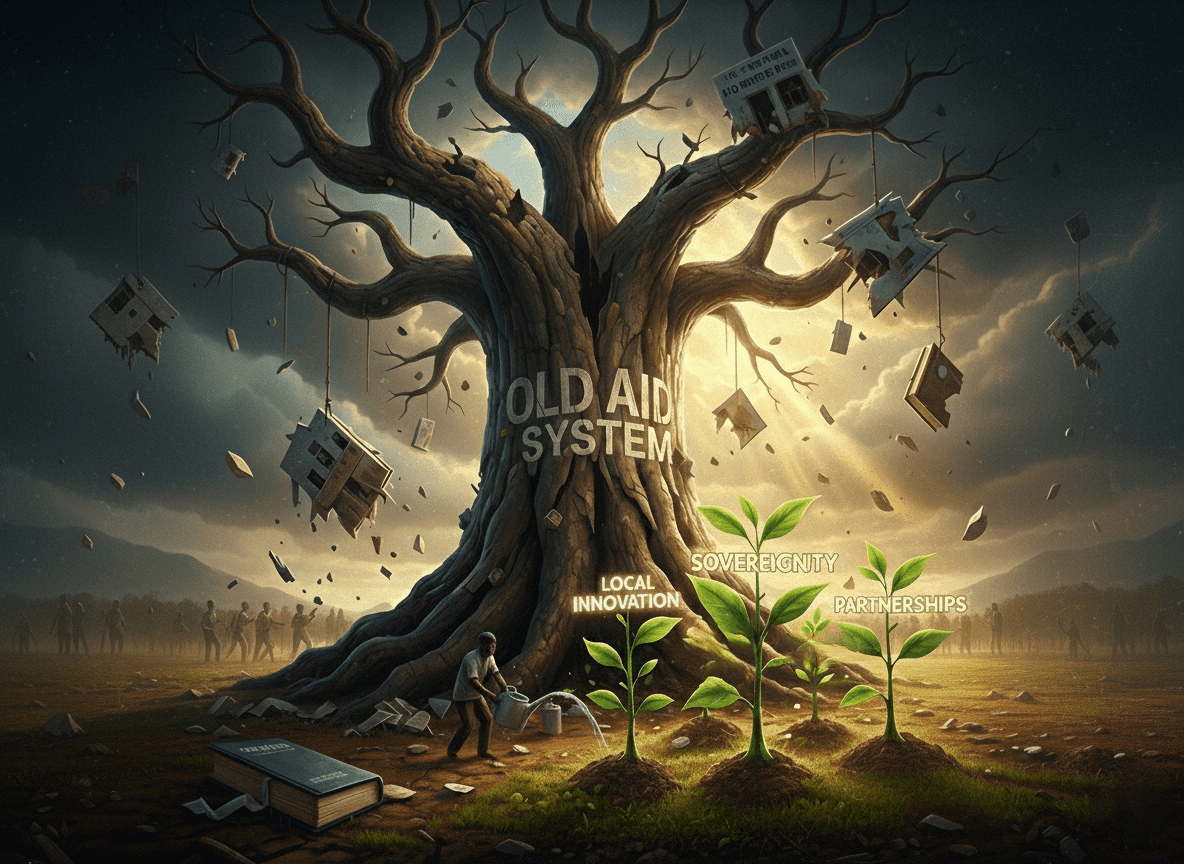

Researchers such as Sara Kinsbergen and Zunera Rana note that the debate is increasingly splitting into two camps: the “improvers” and the “reimaginers.” The former aim to refine the current system of development cooperation by limiting the damage of the cuts, using funds more efficiently, and giving local partners greater say. The second group wants to radically overhaul the system. They raise fundamental questions about power, dependency and the colonial legacy of aid, and advocate full sovereignty and locally led development models.

This divide is visible not only in ideas but also geographically: most improver narratives come from institutions and thinkers in the Global North, while reimagining perspectives are voiced mainly in the Global South. Yet both camps share one conviction: the existing system of development cooperation is no longer adequate. The question is not whether it must change, but how, and above all: who gets to decide.

This search for direction also holds up a mirror to the Netherlands. While ministries and NGOs try to plug budget gaps and save ongoing programmes, young professionals, diaspora organisations, and local partners increasingly feel the desire to rethink the aid relationship fundamentally. No longer as a one-way movement from North to South, but as a reciprocal process of knowledge, responsibility and power.

Wake-Up Call

In October 2025, Vice Versa Global, in collaboration with Sara Kinsbergen and the University of Nairobi, brought together a diverse group of changemakers in Nairobi for the event “Beyond the Development Cooperation Budget Cuts: From Lived Experience to Shared Roadmaps.” From community leaders to academics, media professionals to government representatives, the participants shared their experiences with the recent cuts and reflected on their impact on their organisations and communities. What stood out was the optimism: while many were affected by the sudden shortages, most do not see this as a crisis, but as a wake-up call to fundamentally reform the system.

A clear thread through the conversations was the desire to reclaim agency and ownership: determining research agendas themselves, leading local projects and (re)shaping development cooperation from within their own communities. For many participants, this means critically questioning traditional aid relations in which the Global North often determines the pace and content.

In the midst of Donald’s storm of cuts and geopolitical shifts, another story is emerging. In Nairobi, participants showed that agency, sovereignty and local leadership are not abstract ideals but living possibilities. For the Global North, and for the Netherlands, this means that development cooperation can no longer be one-way traffic. It must be a partnership of equals, with local leaders determining the pace and the course.

The storm continues to rage, yet within its force, new paths, new voices and new ways of collaborating are emerging. In this way, uncertainty becomes not only a threat but also a catalyst for real change.

Box

This article is the first in a series by Vice Versa, before and after the Autumn Symposium of the Kenniscentrum Global Health: The Impact of Geopolitical Changes on Global Health. During the symposium, experts, researchers and practitioners examine how geopolitical shifts influence health systems, research and cooperation, and how we can collectively develop resilient and values-driven solutions.

Edited by Pius Okore.

Leave a Reply