Building Tomorrow in a Broken Today

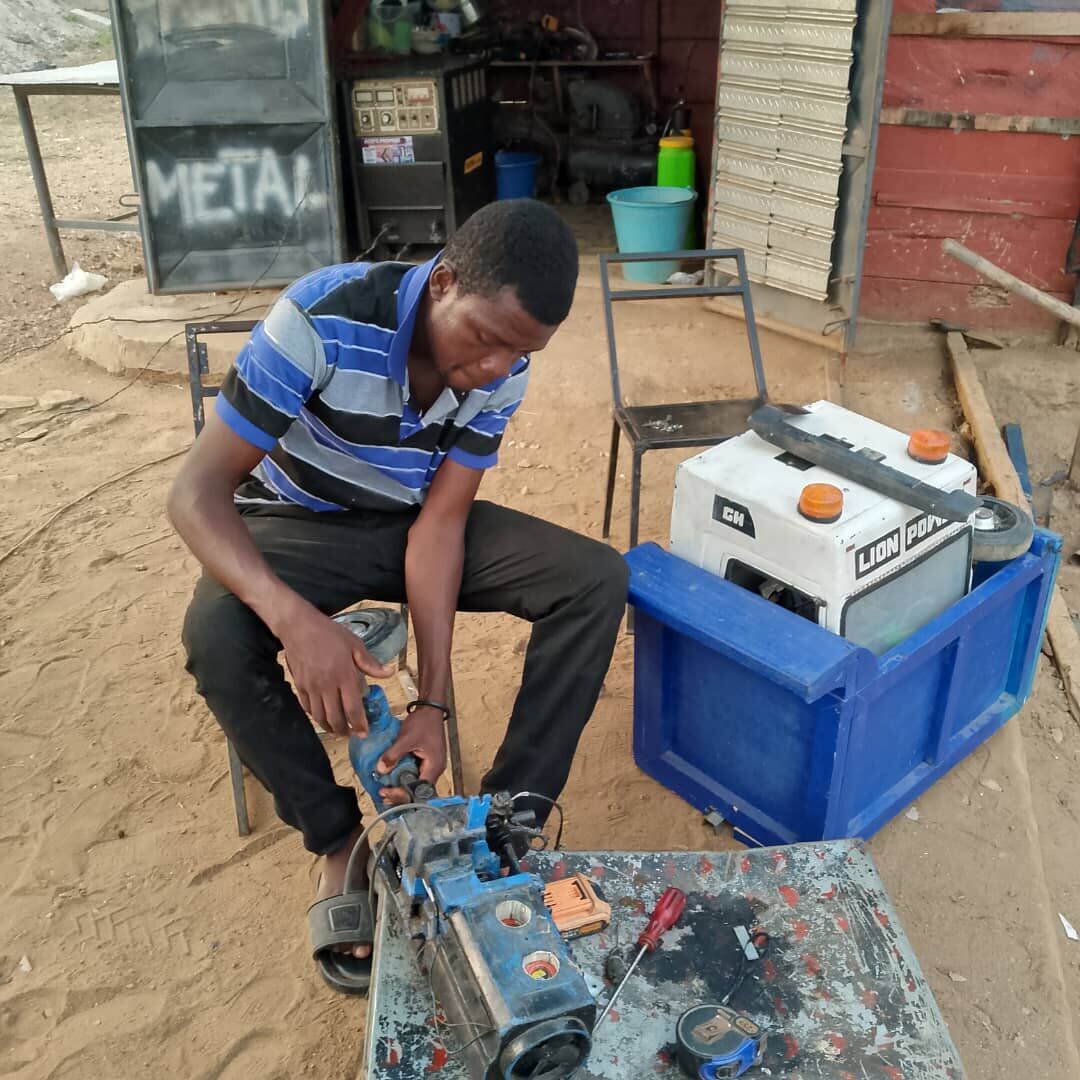

While Ghana remains heavily reliant on imports for approximately 90 percent of its vehicles, sourcing them primarily from industrialized nations such as Japan, the UK, and the USA, Gabriel Boadu from the remote community of Mafi Kope is actively challenging this dependency. Driven by necessity and fueled by ingenuity, Gabriel operates without the aid of the internet, financial backing, or formal training. Despite these limitations, he has embarked on a remarkable journey of innovation, crafting functional machines from discarded plastics, broken electronics, and the power of his imagination. His work not only showcases resourcefulness but also highlights the potential of sustainable practices in vehicle production, offering a glimpse into a future where local ingenuity can contribute significantly to the country’s automotive landscape.

Invention in the Absence of Infrastructure

In a country wrestling with economic turmoil, escalating youth unemployment, and an excessive dependence on foreign imports, Gabriel Boadu’s journey emerges as a rare and subversive counter-narrative. Hailing from the neglected fringes of the Afram Plains in Ghana, in a village where the flicker of electricity remains a luxury and internet access is but a distant dream, Gabriel is quietly crafting a grassroots innovation that national policies frequently overlook.

He originates from Mafi Kope, a rural settlement in Ghana, where the aspirations of stable infrastructure and the conveniences of the digital age seem like a far-off fantasy. This hauntingly beautiful landscape, characterized by verdant fields and a profound sense of isolation, has been long forsaken. Born the youngest of nine siblings, Gabriel’s beginnings were etched against a backdrop of hardship. While some of his older siblings managed to navigate their way through school, his own educational path was abruptly halted, heavily weighed down by the relentless grip of poverty and the encroaching frailty of his parents. In this environment, hope flickers like a candle in the wind, yet Gabriel persists, determined to illuminate a path forward.

“I wasn’t that educated. My parents are quite old, so taking care of me through school was quite difficult. But I believe education is not only in books. If you are observant, curious, and hardworking, you can still learn.”

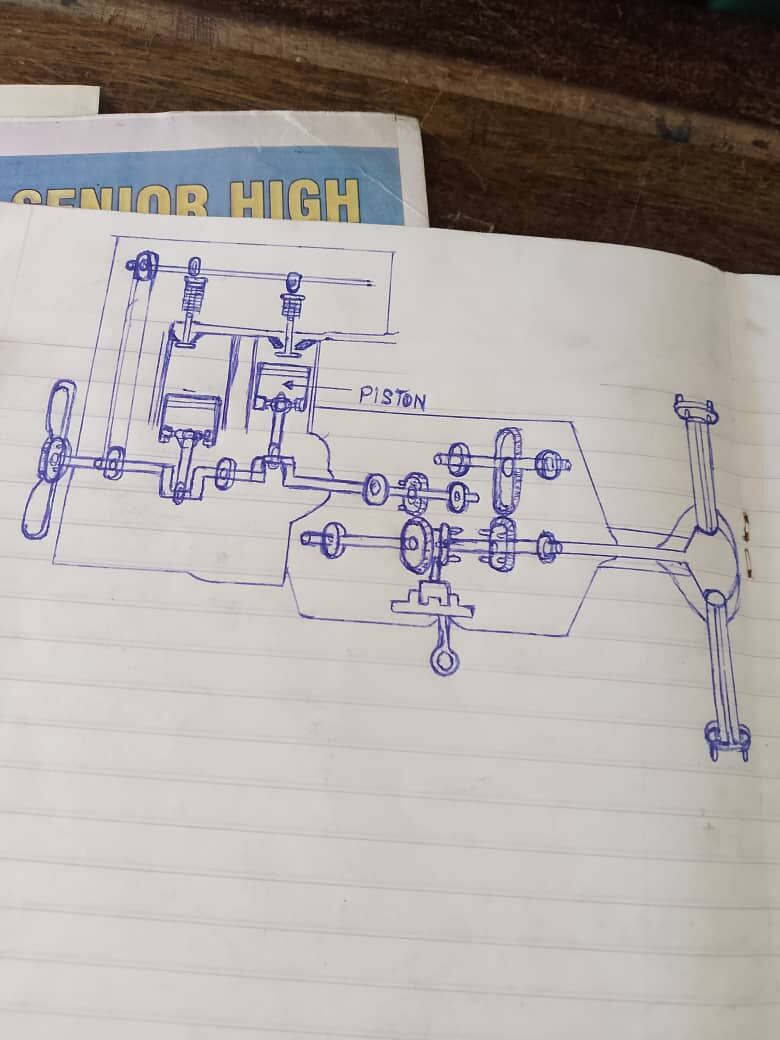

Gabriel’s learning began within the walls of his mind, at just six years old, he would gather sticks to construct simple toys. Even then, he was not satisfied with replication, he was reaching for reinvention. He constantly questioned the reality around him, refusing to accept that hardship was a normality.

“Why can’t we do something quite different from what we are already doing? Should our lives revolve around poverty?” he asked.

That question became a kind of creed. At eighteen, he saw his first moving car, an ordinary moment for many, but a life-altering revelation for Gabriel. That moment provided a candid visual of the motion and mechanics of a car, which was all he needed to create a fully functioning vehicle. However, Gabriel did not have all the refined automobile part and machinery to create an ultramodern vehicle so he resorted to building his vehicles from discarded waste. In his eyes, the trash heaps held an endless possibility waiting to be born.

Machines from the Margins

In the cracks of neglect, Gabriel has invented several machines, like the cooking oil powered generator, truck, and car to make life easier for the indigents in Mafi Kope. Among his most transformative inventions is a generator made almost entirely from discarded plastic. But what makes it remarkable is it’s fuel. Gabriel powers it with ordinary cooking oil, an everyday item in the village, rather than expensive imported fuel that most locals cannot afford. That generator now serves as the heartbeat of the village, charging mobile phones and powering basic lighting in homes that have never known a reliable electricity supply.

“I use cooking oil to power the generator, because that is what we have here. But I’m still experimenting. I want to find something even cheaper, so that everyone in my community can benefit.” Gabriel says.

His inventions also carry messages which are tools of both function and philosophy. One such creation is a compact car powered by coins. Once a coin is inserted the vehicle springs to life. Its travel distance is calibrated to the value of the currency. The system is both clever and symbolic. It mirrors the economy he dreams of, where value is both understood and accessible, even in a place where money is scarce.

He has also built a tipper truck rigged with a two-tiered security start-up system that can only be activated using a Ghana Card.

“I was thinking of how technology could meet our own identity system. If we are talking about national development, it has to include everyone, even people like us in the village.” Gabriel explains

His more ambitious projects stretch the limits of imagination and materials. He has constructed a helicopter and a ship using nothing but broken plastic containers, salvaged parts, and instinct. The helicopter, he believes, could fly, if only he had access to the parts needed to stabilize and test it properly.

“The problem is materials; I can’t get them. I try to improvise, but sometimes it’s not enough.” he laments

Gabriel’s dream is to produce enough vehicles and generators that can power the entire community and by extension power the entire country.

The Irony of Imports and Innovation

Ghana stands at a crossroads. The country imports almost all of its vehicles nearly 100% while grassroots talent like Gabriel’s remains unnoticed. Worse still, recent reports allege that many stolen vehicles from the U.S. and U.K. end up in West Africa, with Ghana listed as a destination. These revelations not only endanger the nation’s diplomatic ties but cast a shadow over our reliance on foreign goods.

Meanwhile, Gabriel’s workshop sits in the dirt, powered by faith and plastic waste. His work poses uncomfortable questions:

What does it say about Ghana that a young innovator must beg for scraps while the country spends billions on imports, many of them second-hand, some stolen?

How many “Gabriel” have we overlooked because they live beyond the cities, speak no English, and lack academic degrees?

A Prophet Without Tools

Despite the lack of financial or government support, Gabriel has not given up. He keeps a thick notebook filled with sketches of machines not yet built. He wants to train others, expand his work, and someday build a lab in his village. But dreams without materials are just ink on paper.

“Finance has been a major problem for me. There is no work or job here that can actually earn you a good income to go outside and buy these materials.” he says

Regardless of these challenges Gabriel is still positive that Africa particularly can produce his own vehicles and essential machines to be more self-sufficient.

“When you look at the whites, it is God that created them. The same God created we Africans and myself. So, if they are able to produce all these sophisticated things, why can’t I also do the same?”

Gabriel is grounded in necessity. He is asking for a chance. A grant, workshop, mentorship and a seat at the table of national innovation. In the silence of rural Ghana, his message to the youth rings loud.

“To the youth out there, I will advise that you should keep fighting, keep dreaming. Little by little, if we are able to put our heads together, have faith in God and believe in ourselves and what we do, we will be able to actually produce something for this country.”

Conclusion

Gabriel embodies the radicalism of self-determined innovation. His machines, forged from detritus and driven by need, disrupt the dominant narrative that equates technological advancement with foreign intervention. In reimagining discarded material into utility, he reclaims both agency and authorship over the tools of progress. His work is inventive and an epistemological resistance, challenging the frameworks that render rural genius invisible. In each prototype lies an assertion that Africa’s future can be assembled from within, not in spite of scarcity, but precisely because of it.

Leave a Reply