The concept of free movement of people within Africa, promoted by the African Union (AU), is reshaping the lives of many — especially migrant women in Uganda. With its long-standing support for regional integration and open-border policies, Uganda has become a destination where women migrants are finding new beginnings through education, entrepreneurship, and leadership.

AU Agenda 2063 seeks to allow visa–free entry for African citizens, promote continental integration, and ease the movement of people across Africa for trade, tourism, and work

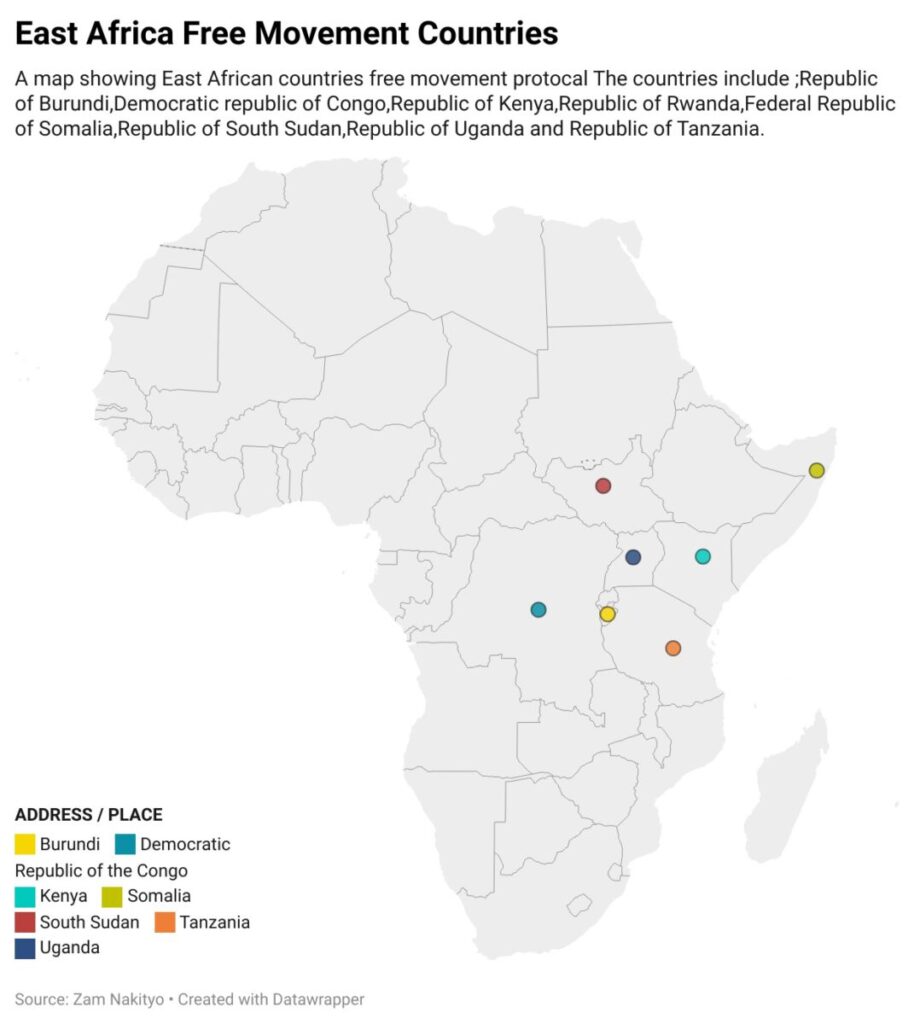

The East African Community (EAC) free movement protocol was established to promote regional integration and co-operation for economic, political, social, and cultural development.

Background

Globally, women migrants have remained a significant demographic, making up 48.1% of migrants in 2020, compared to 49.4% in 2000. According to UNHCR data, approximately 51% of Uganda’s migrant population is women, meaning about 870,000 women migrants reside in the country, with women and children comprising 79% of the total migrating population.

The UN has outlined conventions and recommendations to safeguard the rights of women migrants, including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), often referred to as the “Bill of Rights for Women,” which provides a framework for developing gender-responsive migration policies. General Recommendation 26 on Women Migrant Workers, an extension of CEDAW, offers specific guidance on gender-sensitive migration policies.

https://www.datawrapper.de/_/DZtRH(Link shows a map of East African states who are implementing the free movement protocol)

Across Africa, women are moving across countries, across borders, and across personal boundaries, rewriting stories of strength, skill, and social change. Uganda, known for its progressive stance on regional integration and open-door policies under frameworks like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and the AU’s Free Movement Protocol, has become a fertile ground where many migrant women are sowing seeds of hope.

Migrant women in Uganda are rewriting their stories of perseverance, fortitude, and victory far from the places they previously called home

Health Advocacy Beyond Borders

Francine Ziruka Mwozi, affectionately known as Mama Francine, is a Congolese mother of seven who resides in the centre of Kitebi, Wakiso District. She greets guests with a pleasant grin, surrounded by people of all various kinds, wearing a kitengi blouse and skirt, and wearing a kitengi headband on a cold Wednesday morning.

She has devoted her life to using entrepreneurship and health advocacy to improve the lives of migratory women since arriving in Uganda in August 2011.

“There was no other country between Congo and Uganda, so crossing the border wasn’t complicated,” she says. “We arrived here by bus. We only needed to prove that we were Congolese. After being designated the chancellor of Health in All Refugee Nationality Communities in Africa, Mwozi, a social worker and community administrator back home, still works as an HIV counselor today. She performs her duties without interruption and with pride. She smiles and adds, “I’m still a social worker, and my journey didn’t stop at the border.’

The goal of the January 2018 adoption of the AU Protocol on Free Movement of Persons is to gradually implement the rights of establishment, residency, and free movement across Africa — a step that directly impacts opportunities for migrant women in Uganda and beyond.

Touch and Smile Development, a licensed community-based organization founded by Mwozi, offers health services like HIV counseling, training for hairdressers, tailoring, soap making, and child nutrition programs.

“What pushed me to start Touch and Smile Development was a personal experience,” She says. Shortly after our arrival in Uganda, my son became ill. At the time, I could only communicate in French and Swahili, so I hurried him to the hospital. I was incomprehensible, and getting medical attention became difficult. I came up with the notion to launch a business that aids people in similar circumstances.

Since its inception, the group has provided emotional support and counseling to women at hospitals such as Kiruddu, Mulago, and Bbosa Clinic. Through entrepreneurship, Mwozi enables Ugandan and migrant women to start again.

On specific market days, we sell the liquid soap that we train women to make. The money raised is reinvested in the organization to help us provide food and other necessities to members who are in need, “she says.

The organization collaborates closely with hospitals and village health teams to extend services to underserved communities.

“When we organize health camps, we write to hospitals asking for doctors to volunteer. That way, people can obtain medical treatment without the exorbitant costs, Mwozi adds.

Beyond providing basic services, she promotes economic empowerment and inclusive development. “If you’re a migrant with the right qualifications and documentation, you can get good-quality jobs, “she continues. I’ve used the second chance that Uganda gave me to help others.” As a leader, that’s what matters most, and Mwozi has always valued international cooperation.

She describes how she was able to travel, participate in regional leadership forums and collaborate with other female leaders throughout Africa because of the East Africa Common Market protocol 2010 that Grants citizens of EAC partner states the right to move freely, seek employment, and reside in any other partner state Recognizes the right of establishment, allowing women to start businesses or professional practices.

Education and Leadership Across Borders

Thanks to the EAC’s commitment to free movement and educational access, young women like Sabrin Rizgala are not just crossing borders; they are crossing into leadership, turning migration into a journey of purpose and possibility

A South Sudanese student at Victoria University in Kampala, Sabrin Rizgala, has transformed her experience of migration into a path of leadership, education, and hope.

In February 2014, Sabrin and her family moved to Uganda from Rokon in Juba.

Because of continental frameworks that enable students to study throughout Africa, Sabrin’s educational path demonstrates how policies would allow students to access the best learning opportunities without being constrained by boundaries.

“We migrated in search of quality education,” she continues, “my father wanted us to have access to better education, which we have finally got here,” she said.

Sabrin tells the story of how they took a bus to Uganda, arriving in Kampala, the country’s capital. She says they were assisted in the process of moving by a previous tenant in South Sudan who had a son in Kampala. Sabrin, who is currently working towards a Bachelor of Arts in Media Studies and Journalism, feels that her experience as a migrant has benefited her.

Since the university accepted her and has always welcomed international students regardless of their status, she maintains that being a migrant did not exclude her. “I have never encountered any discrimination”, Sabrin continues. Having been voted President of Victoria University’s South Sudanese students’ Association, Sabrin is not just a student but also a leader. She claims that this job has made her feel at home by providing her with a platform to use her rights as a human being rather than as a migrant.

She wants to use her expertise in journalism to spotlight the experiences of migrants like herself and to serve as a voice that unites people from different backgrounds. “I want to use my career to tell stories that matter and help people understand each other.” Additionally, Sabrin supports free mobility across African nations, calling on leaders to facilitate cross-border travel and settlement for Africans.

Migrant women in Uganda, like Sabrin, are contributing to Africa’s academic landscape by attending institutions abroad, earning scholarships, and building transnational networks. Thanks to the African Union’s Educational Mobility Program and the EAC Gender Policy (2018), which ensures that free movement is accessible and equitable for women and girls, these policies don’t just allow movement—they empower women to lead and prosper regardless of their country of origin. Such frameworks support the academic success of migrant women and help them form connections that benefit the continent as a whole.

Leave a Reply