The Taste Of Home In Every Bowl

In Ghanaian culinary culture, few pairings are as iconic and beloved as akple and okra soup. This combination represents tradition, sustenance, and identity. To understand its significance, one must trace its roots, its evolution, and its place across Ghana’s diverse communities.

During a field episode of Green Africa, a program that explores agricultural innovation and rural livelihoods, I met Kingsley Ametor Sosu, an okra farmer whose perspective brings depth to this familiar crop. To many, okra is an ordinary vegetable however to Kingsley, it is a crop that holds the potential to redefine small-scale agriculture in Ghana.

Akple and okro soup

Akple and okro soup

A Farmer’s Journey Rooted in Local Wisdom

Across Ghana, “okro” forms part of the country’s food heritage. In the Volta Region, it complements “akple”, the soft maize-based dough served with okra soup. Beyond its culinary value, the crop carries equal economic weight. Thousands of smallholder farmers depend on it for income, while households across the country rely on it as an affordable, nourishing staple. Kingsley is part of a young generation of farmers preserving this legacy. After senior high school, he abandoned his dream of joining the military to take up farming, a decision he says was shaped by his desire to remain rooted to his traditions.

“Farming okra gives me independence and connects me to our traditional ways of doing things. I can’t watch our indigenous foods disappear while everyone is busy chasing white-collar jobs. Okra is something I can rely on; it always gives back.” He said.

Today, he cultivates several acres, guided by experience and ancestral knowledge of seed selection and planting. He proudly lists his local varieties: Sebejo, Kontembratem, and Badavi each distinct in form and resilience.

“Sebejo, a direct translation of the deer looks like the horn of a deer” he explaine, that’s how it got its name. Kontembratem grows fast and fruits quickly, but dies early, a reminder of how quickly fortunes can rise and fall in farming.”

These indigenous varieties carry stories beyond the farm. They have morals of life, poetics resonance and substance value for the local people of the Volta region.

Kingsley Ametor Sosu on the left

Kingsley Ametor Sosu on the left

The Economics of Green Gold

Okra may not enjoy the global attention of cocoa, but for farmers like Kingsley, it offers quicker returns.

“You wait years to harvest cocoa, but with okra, you can sustain yourself regularly. I harvest every three days, so I’m never hungry.” he noted

The crop’s short growth cycle which spans about two months from planting to harvest allows multiple yields each year. “At the peak, I get 25 to 28 bags. When demand is high, each bag can sell for 600 to 1,000 cedis. That keeps my family going.” He said.

Kingsley also points out how okra prices follow the rhythm of Ghana’s staple foods.

“When maize dries, prices rise. People eat more akple, banku, and kenkey and they always want okra stew.” He explained.

This link between maize and okra shows how intertwined Ghana’s food systems are one crop influencing the value of another.

Farming Against the Odds

Despite its promise, okra farming is full of challenges. Floods from nearby dams often submerge fields, wiping out crops within hours.

“You can’t control the river. Sometimes it floods without warning, and you lose everything.” Kingsley said.

Pests like whiteflies and armyworms also threaten yields, while changing weather patterns disrupt growth.

“When it stays cold too long, the plants don’t do well. They need both sun and rain.” He said.

He also worries about unsafe pesticide use. “Some farmers use chemicals meant for cocoa, that’s dangerous because okra is eaten fresh.”

Kingsley works closely with agricultural officers to identify safe inputs and ensure proper spacing for ventilation.

“I will rather lose some yield than poison what people eat,” he said.

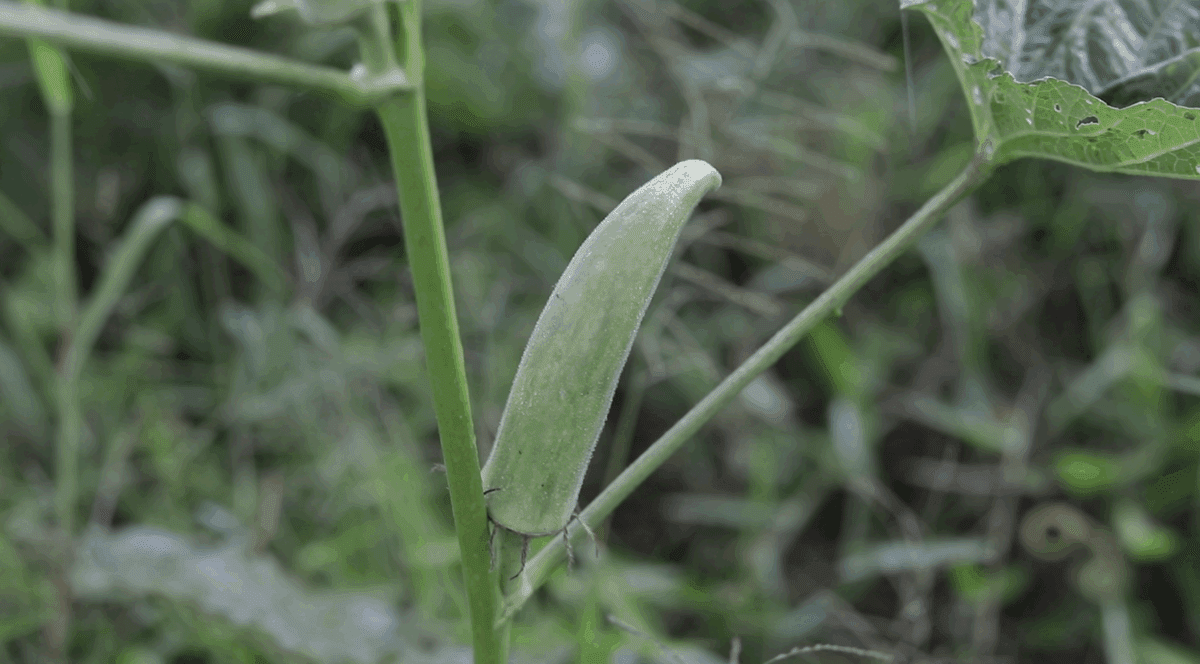

Okra

Okra

The Culinary Origin of Akple and Okra

Historically, akple and okra soup have been staples of Ewe cuisine, however over generations, the pairing of akple and okro has evolved into a cultural symbol of home and hospitality among the Ewes, spreading to neighboring regions and influencing other Ghanaian dishes like banku and okro soup. Today, whether served in the urban or rural areas, akple with okra soup continues to embody the soul of Ghanaian culinary tradition.

Conclusion

Okra remains one of Ghana’s most underappreciated crops. It matures fast enough to keep incomes steady, and provides income for thousands of farmers. Yet, it receives little structured support or research attention. With better investment, training, and access to markets, okra farming could offer young people a sustainable path to livelihoods.

Leave a Reply