What Ghana’s Young Believe About Religion Today

Justice Baidoo and Efo Korku Mawutor

Faith is no longer a given for Ghana’s youth; it is being rewritten. In a society where rituals clash with modern realities, young people are reshaping religion to serve conscience, empathy, and community, creating a vision of belief that is as practical and plural as the world they inhabit.

A church bell tolls in the Holy Spirit Cathedral in Accra, Ghana; a call to worship, to order, to a tradition spanning two millennia.

In Ghana, where faith has long shaped society, a subtle transformation is underway. For the country’s youth, its largest demographic, religion is no longer inherited, it is being renegotiated, a source of solace, tension, identity, and scrutiny.

This is a story told through their voices: a priest, a community activist, a creative, and an imam, each navigating faith in a world where its future may depend less on dogma and more on lived experience.

The Holy Spirit Cathedral Adabraka, Accra, where Fr. Michael serves as a priest

The Long Road of Passion and Purpose in a Secular Age

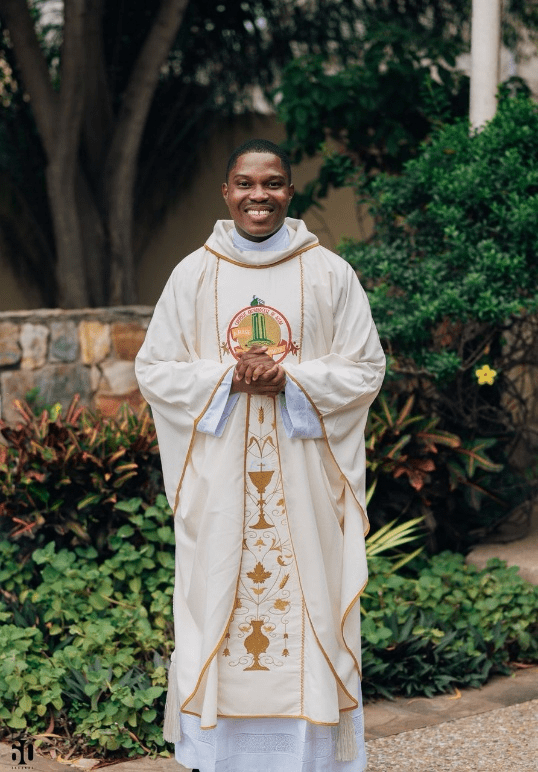

Reverend Father Michael Amponsah is a young priest in an ancient institution. At just 28, and ordained only three months ago, he is a rare anomaly. He devoted ten years to formation: a year of aspirancy, four years of philosophical studies at St. Paul’s Catholic Seminary, and another four at St. Peter’s Regional Seminary, interspersed with pastoral work. In that time, his peers could have earned a PhD in a conventional academic track. Yet, he chose this path when many commentators predicted religion’s decline.

What drives a young man like him to take on such a demanding journey?

“Number one is passion,” Fr. Michael says, calm and assured. “Religion may be waning for some… but it still holds relevance for people of faith, for those who see human existence as more than just material.”

Passion alone, he notes, is not enough. A true vocation requires a “sense of a call,” not necessarily a dramatic vision, but a quiet, refined desire to serve, coupled with “dedication and commitment,” virtues vital on a road demanding immense spiritual, human, and intellectual investment.

“If you don’t have the passion for this… in no time you will burn out and find little fulfilment in ministry,” he explains.

His conviction is sometimes tested by the very narrative he seeks to counter. “Some priests would see you in the seminary and comment, ‘By the time you finish, the pews will be empty.’”

Yet his early experience defies that gloom. In just three months of active ministry, he has found a flock eager to be shepherded; even a minister from another Christian denomination sought his counsel.

The youth, he notes, are a complex audience. In his community, he observes a “strong youth presence.” Young people are searching for guidance and often feel more comfortable approaching a younger priest they believe is “in touch with the reality you’re going through.”

He sees two currents in what young people seek spiritually. Some are drawn to tradition, the rituals passed down through generations; routine prayers, Mass, and worship. Others gravitate toward the “miraculous… the charismatic,” craving passion, singing, and movement. “If the youth are in a place where they don’t see passion… they may drift away,” he says.

For Fr. Michael, hope lies in the few with dedication. “When you find one youth with voice, with the willingness to sacrifice for the good of the church… then we have confidence. The future still holds hope.”

Fr. Michael poses for a photo dressed in his priestly regalia

The Pragmatism of Faith

If Fr. Michael’s world is rooted in deep tradition, Rabiatu Yakubu’s is one of transformative action.

Born and raised in Sabon Zongo, a deprived urban area in Accra, Rabiatu is the fifth of six girls raised by a single mother. Her faith is Muslim, but her mission is human.

“I am committed to changing the narrative of my community, letting young people believe in their power to change their lives and transform their communities,” she declares.

Her vehicle is the Radiza Mentorship Initiative, a structured program that trains young people in Zongo communities and Islamic schools on leadership, sustainability, and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. It includes workshops, factory tours, and speed mentoring sessions.

What stands out, however, is her operational philosophy. When asked why she collaborates with Christians, her answer is immediate and unequivocal:

“Religion has never been a deciding factor. It has never been on the list for me… I looked for people. I looked for humans. I didn’t look for Christians or Muslims. I looked for people who believed in what I was doing.”

Her perspective is rooted in a simple, profound theology: “If God or if Allah… wanted us to be in one religion, he would have created us to be in one religion. He created us as we are… Just be human and do what you can to get closer to your God.”

For Rabiatu, the real differentiator is values, not creed. “You can have a Muslim who doesn’t respect humans or a Christian who doesn’t respect… I can’t work with you. But if you are praying, however you pray, and you share the same values, I am with you. For me, it’s the value you bring to the table, not how you pray.”

This values-first approach shapes her view of global religious conflicts. Watching wars in Ukraine and Gaza, she sees the loss of human potential.

“Children with dreams and ambitions that could change the world are being killed. I don’t think religion should be the cause of that.”

Her vision is a generation empowered to solve its own problems rather than wait for external saviours. “We are looking at a generation that, when faced with a problem, says: we know we can fix it, and we fix it.”

Rabiatu, making her way to the Mosque in Sabon Zongo, Accra

Staging Unity in a Divided World

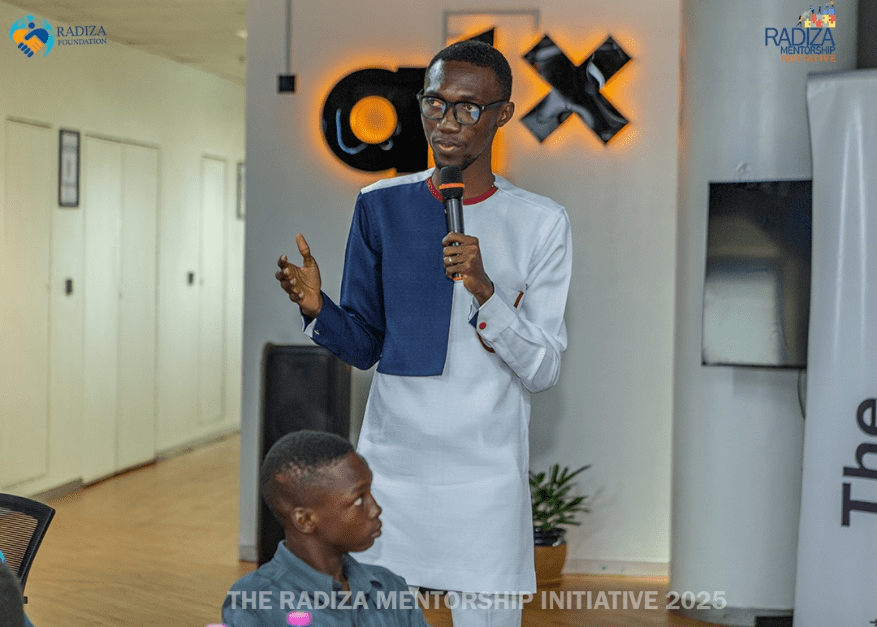

Smart Takyi Nixon, a communications professional, playwright, and youth advocate, has been volunteering for over 12 years. He is a living bridge between the worlds of Fr. Michael’s tradition and Rabiatu’s transformative action. A devout Christian, he has consulted for free and served as facilitator and mentor for the Radiza Foundation.

His involvement is deeply personal. Born and raised in Nima, a Zongo community, he learned “brotherhood… from my Muslim brothers.” He recalls, “They gave me food without asking what type of religion I had.” This lived experience often contrasted sharply with the message he sometimes heard in church: “Do not be yoked with unbelievers.”

“Advocacy is not religion-based,” Smart asserts. “Advocacy is access. It’s the willingness to hold another person’s hand and say, I have long legs. I’ll put you on my shoulder and walk you through the stream.” And Smart does have long legs—both metaphorically, at heart, and literally.

This philosophy is tested in his professional life as a playwright staging social and commercial plays in a church auditorium. Some clients refused tickets solely because of the venue. “I don’t see that as a problem,” he says, though he acknowledges the business challenge. He has learned to think like a businessman, not just a friend, recognizing that not everyone will support his work.

His experience with cross-religious attendance is revealing. Muslim friends from Zongo often show up out of a sense of fraternity, sharing his event flyers more than some Christian friends. He sees this as testament to the camaraderie forged in the community.

Reflecting on today’s youth, Smart observes they are “gravitating toward more understanding,” fuelled by access to information. “A man of God can say something, and they are like, no, this doesn’t sit well with me.” This critical engagement, he suggests, mirrors the Bereans in the Bible, who examined the scriptures to verify what they were taught.

Yet he offers a cautionary note: “Religion is gradually losing its hold on people,” he observes, pointing to leaders who “are continually failing us.” His advice to young people, however, is not to abandon faith. “Believe in something,” he urges. “There is a level of darkness you will experience… and it takes a higher calling to draw you out.”

Smart Takyi Nixon speaking at the Radiza Mentorship Foundation

Faith as a Shield and a Compass

From within the Sabon Zongo community, Imam Ali Ibrahim offers a ground-level perspective. A tutor and head of an Arabic institution, he speaks of a community of diverse ethnic groups living in relative harmony, though grappling with challenges like youth drug abuse—a scourge recently curtailed through the intervention of the local chief.

He laments the scarcity of visible role models. “Most of the people we looked up to, who succeeded and came from Sabon Zongo, are no longer with us in the community,” he observes. Opportunities exist, he adds, but the “endurance” to rise above present struggles is often lacking among the youth.

It is in this context that he sees the Radiza Mentorship Initiative as a “laudable” intervention. Asked about Christian mentors like Smart participating, his response is pragmatic and unifying: “I don’t see it as a problem… Look at the impact on the generation. They are helping us, we are helping them, and together we build a community we can all be proud of.”

Imam Ali’s perspective on youth and faith is both concerned and compassionate. “We need to stand on our feet based on faith and religion,” he says, noting that many young people treat faith superficially rather than as a deep guiding principle. “Lack of knowledge makes my people perish,” he warns, but he stops short of blaming the youth entirely, pointing instead to their environment and company.

He calls on religious leaders and elders to “wake up” and provide the guidance necessary to keep the youth on a steady path.

Children in a Makaranta class at Malam Ali’s Islamic School

A Tapestry of Belief and Action

The stories of Fr. Michael, Rabiatu, Smart, and Imam Ali capture the contemporary Ghanaian religious experience. It is not a simple narrative of decline or revival, but a rich mosaic of searching, service, and scepticism.

For Ghana’s youth, faith is being distilled to its essential components. For some, like Fr. Michael, it is a passionate, lifelong vocation rooted in enduring tradition. For others, like Rabiatu, it is a motivational force that drives tangible community impact, where shared values outweigh religious labels. For bridge-builders like Smart, it is a call to universal service that transcends the walls of church or mosque. And for community anchors like Imam Ali, it is a vital compass in a stormy world, even if not always followed.

Together, they illustrate why faith-based development matters more than ever. In a world of fragmented identities and global challenges, faith structures provide unique networks for mobilisation, channels of hope, and a language of moral purpose.

The future of faith in Ghana will not be measured by the number of worshippers or the grandeur of rituals, but by its depth of engagement with the real, pressing lives of youth. It will rely on its ability to be, as Rabiatu embodies, a force that empowers young people to “believe in their power,” and as Smart advocates, a foundation upon which to “believe in something” that anchors them through life’s inevitable storms.

Pews may change, music may modernise, and questions may multiply, but the search for meaning—and the desire to act for good—remains, for Ghana’s youth, a faith all its own.

This mini-series was proudly sponsored by the Shared Futures Programme of Kerk in Actie. Shared Futures partners with local actors to strengthen interfaith cooperation among young people, helping communities move from coexistence to collaboration through practical, everyday solutions.

Leave a Reply