Youth Voices on Religion’s Evolving Role in Ghana

Faith for Ghana’s youth is no longer confined to mosques or churches. It has become a language of empowerment, guiding young people to leadership, ethical action, and advocacy. By integrating belief with practical initiatives, they are reshaping communities and showing that spirituality can inspire tangible change.

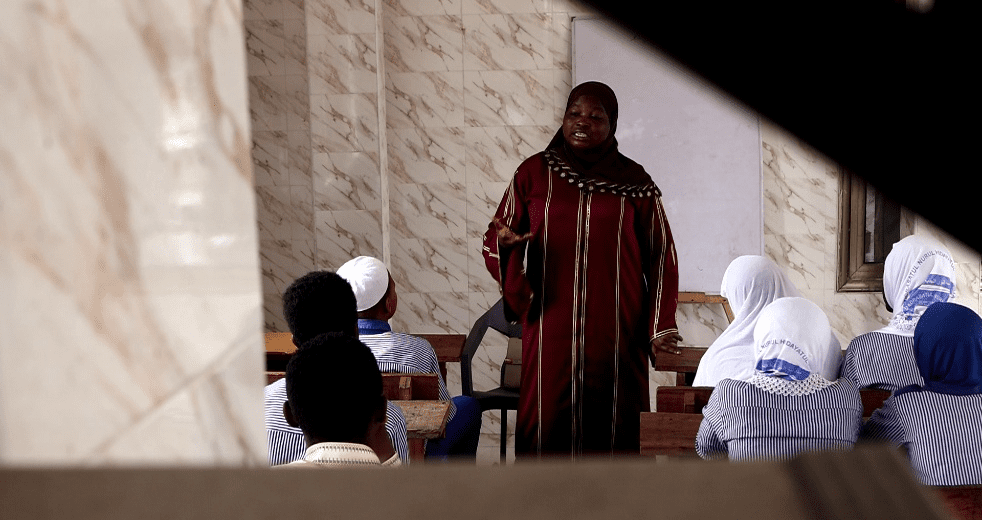

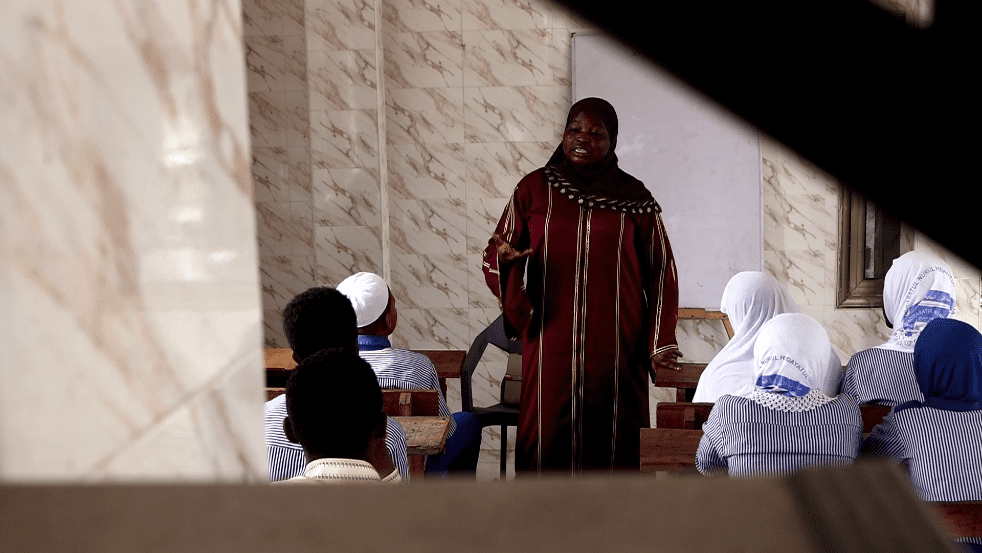

In a small classroom tucked between the narrow lanes of Sabon Zongo in Accra, Rabiatu Yakubu addresses a group of teenagers. Their eyes follow her as she speaks, not of scripture or ritual, but of sustainability, leadership, and self-belief.

“I am committed to changing the narrative of my community,” she says firmly. “I want young people to believe in their power to transform their lives and communities.”

Rabiatu, a young Muslim woman raised by a single mother and now founder of the Radiza Foundation, is part of a new generation of Ghanaians redefining what religion means and what it can achieve. For her and many of her peers, faith is no longer confined to the pulpit or mosque; it is a language of social action, unity, and personal empowerment.

Through her flagship Radiza Mentorship Initiative, Rabiatu and her team move between Islamic schools, local industries, and mentorship circles.

“Our flagship project is a three-phase structured mentorship,” she explains. “We conduct trainings in schools and Makaranta across our Zongo communities on positive citizenship, leadership, and sustainability. We equip young people to become responsible citizens and raise awareness of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.”

Yet what truly distinguishes her approach is not just the curriculum, it’s the company she keeps.

“Yes, I’m Muslim,” she smiles, “but I work with Christians. Religion has never been a deciding factor. I sought people who believed in what I was doing; I looked for humans, not Christians or Muslims.”

Her organisation unites mentors from different faiths around a single goal: helping young people see beyond their limitations. In a world where religion often fuels conflict, Rabiatu’s approach is radical in its simplicity.

“If God, or Allah, wanted us all in one religion, He would have made us that way,” she says softly. “Just be human, and do what you can to grow closer to your God.”

Rabiatu teaches children in Sabon Zongo

A Generation Rethinking Religion

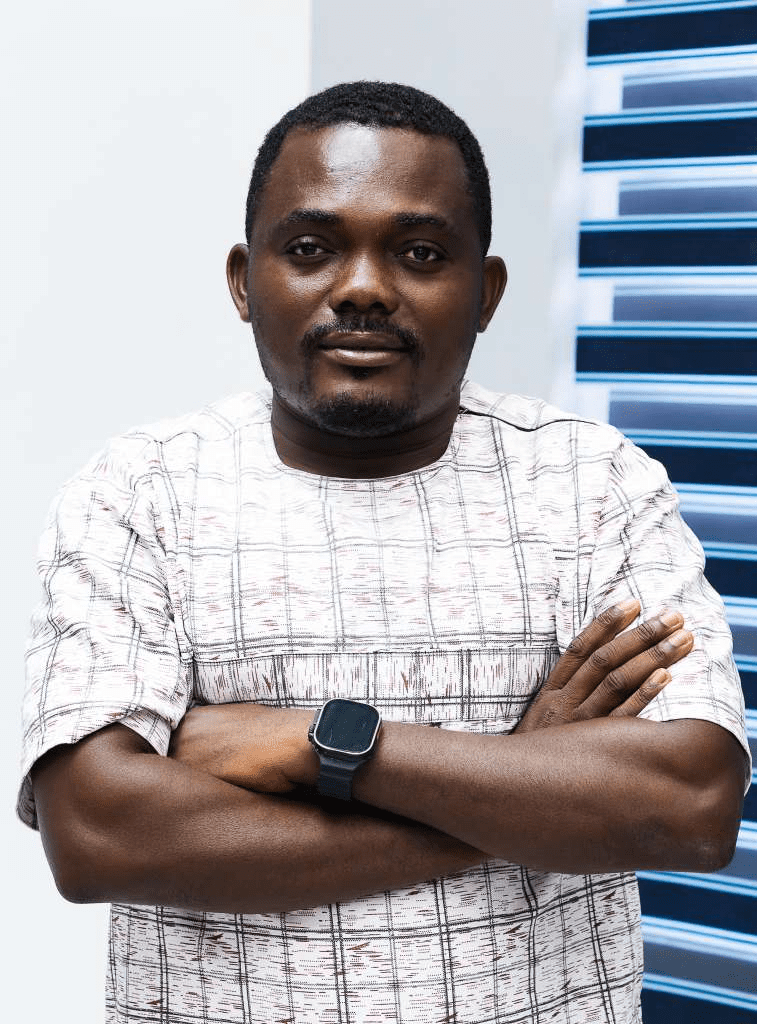

Across town in Ogbojo, Stanley Nii Blewu, a multimedia and investigative journalist, speaks with weary conviction. Raised in a Christian household, his relationship with the church has long since cooled.

“I don’t frequent church on regular Sundays,” he admits. “The last time I willingly went to worship was around 2009. Yes, it’s been more than a decade. But in my heart, I feel I’m a Christian because I live according to the Bible’s teachings.”

Stanley’s words reflect a broader sentiment among Ghana’s urban youth: a desire for personal spirituality without institutional mediation.

“I don’t believe we need to be in church every day to qualify as Christians,” he says. His frustration is not with faith itself but with its commercialisation. “Religious leaders do not teach people the way they should. Pastors prioritise making money over shepherding their congregations. Everything has now drifted to money, money, money.”

For Stanley, the future of faith does not require new sects or flashy movements. “The three main religions in Ghana, Christianity, Islam, and traditional religion, are sufficient. Leaders should teach the Bible without exploiting it for profit.”

His vision is conservative yet reformist: keep the faith, but clean the house.

Stanley Nii Blewu, journalist with TV3, Accra

Faith at the Crossroads of Technology

If Stanley represents a return to integrity, Nasiba Aminu Gariba stands at the opposite frontier; a space where religion is being deconstructed, digitised, and reinvented by a generation raised online.

“Social media has given so many people access,” she says. “Religious people now have free platforms to share their beliefs. But at the same time, people have access to information that challenges religion. They are questioning everything, breaking away from indoctrination.”

Nasiba, a YouTuber and writer, speaks with the measured honesty of someone who has wrestled with belief. “I don’t know what to do with it anymore,” she admits. “Since I was 16, I started questioning whether I really wanted to be religious.”

She laughs lightly, then grows pensive. “At this point, I’m just exhausted because I don’t really believe in heaven or hell. But sometimes I pray because I’m tired… sometimes that’s all you can do.”

For her, religion has become “a spiritual battery… a system to recharge spiritually.” It is less about fear or dogma and more about emotional renewal and inner peace. She is sceptical, but not nihilistic.

“Religion works best when people can customise it to their personalities, goals, and beliefs,” she argues. “It can’t be forced. It should guide, not coerce.”

Looking ahead, she foresees a faith landscape defined by personal interpretation rather than collective conformity. “It’s going to become more individualistic. People won’t care as much about communal religious participation. I think we’ll see more people stepping away from religion altogether.”

And if traditional religiosity fades, what replaces it? “People will become more realistic,” she predicts. “They’ll rely on historical facts and real-life experiences to guide how they think and behave morally.”

Nasiba Aminu-Gariba, content creator and YouTuber

On Brotherhood and Belief

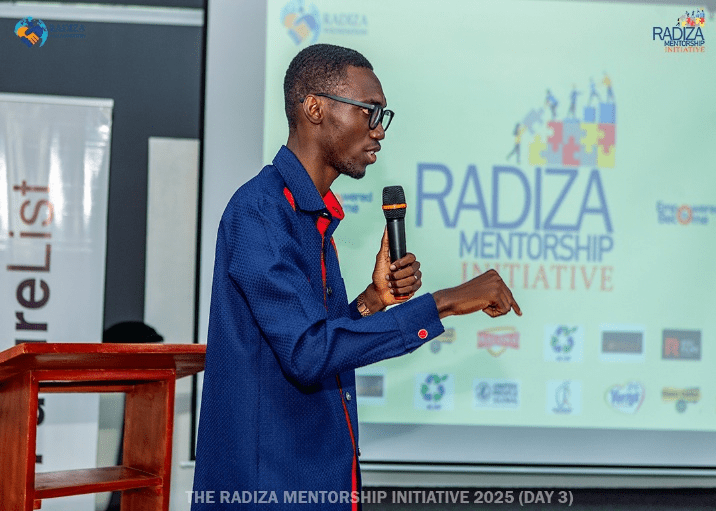

For Smart Takyi Nixon, a communications professional and playwright with over a decade in advocacy, faith is not a dividing line, it’s a shared table.

“I learned brotherhood from my Muslim brothers. I learned love from them,” he reflects. “Though they weren’t Christians, they taught me lessons I wouldn’t have learned otherwise; like sharing food with the people sitting on the bench with us.”

Those lessons, he recalls, often came on the streets, debating football salaries with friends of different faiths. “I was never looked down upon because I was Christian. But in church, a Christian brother might say, ‘Do not be yoked with unbelievers.’ That kind of teaching does more harm than good.”

Smart refuses to see religion as a barrier to empowerment. “We are all one people,” he insists. “Advocacy is not a colour party, not religious, not societal. It’s access, the willingness to hold someone’s hand and walk them through the stream so they can get to the other side.”

His partnership with Rabiatu Yakubu’s Radiza Mentorship Initiative embodies that belief. “When the Muslim-led foundation invited me to mentor youth in Zongo communities, I didn’t hesitate. They gave me food without asking my religion. Why should I care?”

Even small decisions, like opening a session with a prayer, reflect his approach. “Our international partners said, ‘Do it your way.’ The Imam prayed. I’ve never seen advocacy as religion-based. Helping another human is enough.”

Smart’s worldview mirrors a broader trend among Ghanaian youth, blending faith, pluralism, and practical compassion. “Young people today are more understanding. They read, listen, and learn from podcasts and online discussions,” he notes.

His critique of modern empowerment programs is sharp: “Focus on impact, not numbers. Many programs prioritize appearances—photos, attendance—over real transformation. The impact happens in breakout sessions, where people ask questions and find direction.”

Yet he still believes in the spiritual necessity of faith, tempered with honesty. “Religion is losing its hold because leaders are failing us. My message to youth: believe in something. Life has darkness money cannot fill. It takes a higher calling to lift you out of that sewer.”

Almost sermon-like, he adds: “If you’re Christian, serve God well. If Muslim, serve Allah well. Whatever you do, believe in something. There are higher beings we cannot see. Sometimes, it doesn’t take time—it takes God.”

Smart Takyi Nixon speaking at the Radiza Mentorship Programme

A Generation After God?

Sociologists call it the “post-religious age.” In Ghana, it feels more like a re-religious age, where old forms fade and new, humane ones emerge.

These young voices are not rejecting God, they are asking what belief means in a world of inequality, opulent pastors, and viral sermons. Their answers are diverse, but together they sketch tomorrow’s faith: empathy over empire, conscience over conformity.

Perhaps the future of faith is not less sacred, but more human. Perhaps it looks like Rabiatu in Sabon Zongo, telling her mentees: “We are changing mindsets… giving hope and helping them see beyond their limitations and believe in their power to make change.”

In the end, Ghana’s young believers are not seeking new gods, but a new way to believe, a faith that “looks at values, not how you pray,” that “guides, not forces,” one where “we hold another person’s hand and walk them through the stream.”

Where being Christian, Muslim, or otherwise simply means, as Smart says: “Whatever you do, believe in something, because sometimes, it doesn’t take time. It takes God.”

This mini-series was proudly sponsored by the Shared Futures Programme of Kerk in Actie. Shared Futures partners with local actors to strengthen interfaith cooperation among young people, helping communities move from coexistence to collaboration through practical, everyday solutions.

Leave a Reply