A sigh of relief for Uganda’s poor and vulnerable

Laws are created to protect the rights of people and ensure their safety. In spite of this, some rogue law enforcement agencies use them to terrorize and extort bribes. In a recent ruling, Uganda’s Constitutional Court ruled that such an outdated law should be repealed. Hopefully, this will be the first of many steps taken to protect vulnerable people.

The first of November 2016 was the first time I spent behind bars.

The Makerere University community and the surrounding areas were marred earlier that day by violent protests by students after lecturers refused to teach them. As a first-year student, I had sought refuge in a colleague’s hostel room outside the university premises to avoid being arrested by the charged police officers and other military personnel who were on a rampage arresting every student they came across.

As a result of the disruptions, Uganda’s President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni ordered the institution to be closed indefinitely later that night. Students were expected to vacate the premises immediately.

At about 11 pm I set out to return to my hall of residence situated within the university gates. A police patrol van was parked a few meters from my host’s gate. As expected, I was stopped by the police officers who without questioning me, ordered I get under the seats at the back of the van. There were already about seven other young men bundled up.

Upon reaching the police station I was informed that I was being charged with being a rogue and a vagabond. The facts forming the charge were that I was moving around late at night without proper identification. My pleas of being a first-year law student who was yet to receive his university ID fell on deaf ears let alone explaining to them that I had recently lost my national ID.

Two years later in 2018, a suit was brought before the constitutional court of Uganda. This suit challenged the provisions of the Penal Code Act on the offence of being a rogue and a vagabond.

Huge Milestone

In the groundbreaking case of Francis Tumwesige Ateenyi v. Attorney General, the petitioner contended, among others, that the offence was not sufficiently defined as required by the Constitution of Uganda. In addition, the offence was vague, enabling the police to arbitrarily arrest and detain any person in the absence of reasonable suspicion. Further, the provision violated the Constitution’s provision on the presumption of innocence for anyone accused of a crime.

On 1st December 2022, the Constitutional Court unanimously declared part of the said sections of the Penal Code as void and unconstitutional.

The provisions in question were formulated during the colonial period. They served the purpose of suppressing dissent by the natives and restricting their right to liberty as they controlled their movements in certain areas and times of the day. Upon gaining independence, the subsequent administrations maintained the said provisions on unclear grounds.

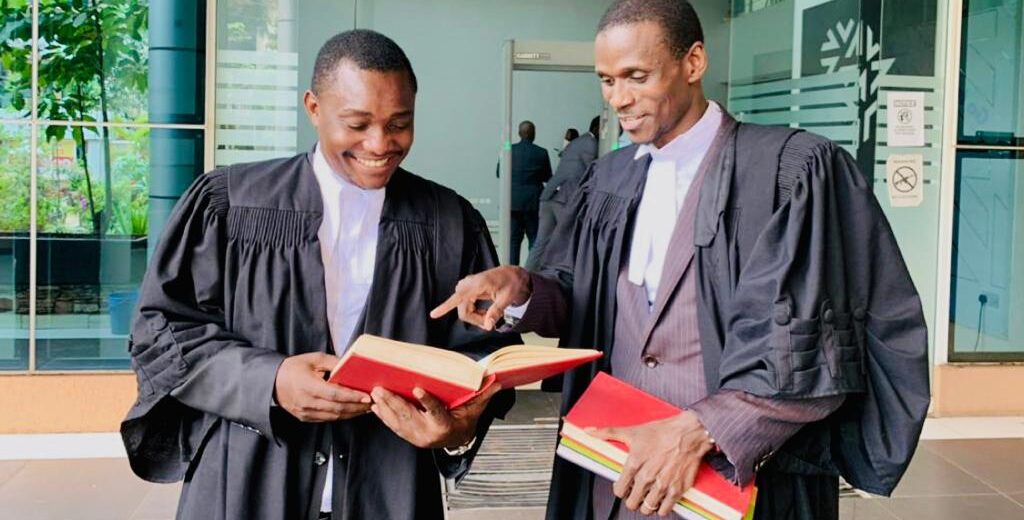

Dr Adrian JJuuko, the Executive Director of Human Rights Awareness and Promotion [HRAPF] was one of the lawyers that represented the petitioner in the above case. HRAPF is, without a doubt, one of the leading human rights organizations that advocate for the rights of marginalized persons in Uganda. These include LGBTI persons, sex workers, and Persons Who Use and Inject Drugs [PWUIDS], to mention but a few.

Upon completing my undergraduate degree, I was sent there under a special internship program. I later served as a legal volunteer for close to a year. During my period of service, I was part of the team that offered legal aid services to marginalized persons.

Looking at the economic situation of Uganda, the youth who form over 70% of the total population are largely unemployed. The few who are lucky enough to be employed are paid peanuts. The rest are pushed to survive between jobs, including sex work, an occupation that is deemed immoral by African standards. Others resort to drug, alcohol and substance use, which turns into an addiction. Poverty is the common denominator here.

Extortion

Marginalized persons formed the majority of the victims of the law on the offence of being a rogue and a vagabond. They were usually arrested during routine operations and night patrols. Most of the cases were resolved at the police station. Not that the police were doing a good job.

Actually, my colleagues and I were met with a lot of resistance from police officers every time we intervened to secure the release of our clients on such charges. This was because our presence as lawyers prevented them from extorting money from the suspects, a practice that had been running since time immemorial.

These occurrences sparked memories of my university days when they demanded Ugx 200,000 for my release on similar charges. However, I was set free two days later on ‘humanitarian’ grounds upon my refusal to pay the bribe.

The Uganda Police Force was quick to respond to the pronouncement. In a statement issued on their website and official social media handles the spokesperson, Mr Fred Enanga, stated that the police were expected to move away from low-level disorders that allegedly criminalized poor people and persons of low status.

In addition, he stated that it was high time the police diverted their resources and time to look at other serious and violent crimes. He concluded by stating that any police officer who is found arresting suspects based on the offence of being a rogue and a vagabond will immediately be subjected to disciplinary action for disobedience of lawful orders. He further requested local leaders and communities to comply with the ruling and cautioned them against acts of vigilantism and mob justice.

To some extent, we can all agree that the victims of the nullified provisions of the Penal Code Act are now able to carry on with their daily lives without much interruption.

However, there are still other laws in existence that perpetrate systemic marginalization. These provisions can still be used in the absence of the nullified sections of the Penal Code. For example, the offence of being a common nuisance is a potential substitute. When I attended a court session recently, the trial magistrate asked the suspects about the charge of being a common nuisance. He asked them why they were sleeping in underwater drainage channels and trenches, yet it was obvious that these youths had no other place to reside. They were consequently remanded to prison until they could provide an ‘appropriate’ answer.

Therefore, the Law Reform Commission of Uganda needs to work hand in hand with other related agencies and departments. This is to ensure that there is a revision and complete overhaul of such regressive provisions of the law as they have no relevance in this time and era.

Leave a Reply