SGBV IN HUMANITARIAN SITUATIONS.

The level of sexual violence increases in humanitarian situations, and as is the norm, women and girls suffer the most, regrettably. A study conducted by KIT and Save the Children International aimed at identifying and attending to the needs and rights of groups affected by this transgression.

‘Before I came to the camp, I was abducted by Boko Haram. We were living in a village (name withheld) with my mother. Then one fighter came to my village and told my mum that if she did not give them her girls, they would kill her. So my mum handed over her girls to them to be safe. We stayed for a year plus in the bush with the boys before coming to town,’ a 25-year-old woman interviewed in Gwoza IDP camp for the Research for Change Project.

For 13 years, the Islamic group Boko Haram has continued to terrorize communities in Nigeria’s Borno state, killing men and boys, and abducting young girls and women. In April 2014, they abducted 276 girls from a government secondary school in Chibok. This act brought to the limelight the little-researched and less-addressed issue of conflict-related sexual violence in humanitarian settings and areas of conflict.

The infamous hashtag #BringBackOurGirls first posted by a Nigerian lawyer not only trended globally but brought worldwide attention to the dangers of ever-present sexual violence in humane situations. According to Amnesty International (AI), this abduction was a small percentage of the total number of people abducted by them. In 2015 Amnesty International estimated that at least two thousand women and girls had been abducted by the group since 2014, with many of them being forced into sexual slavery.

Different actions have helped bring about a growth in the number of programmes that seek to find solutions as well as prevent sexual violence in humanitarian and conflict settings. Nonetheless, it remains a complex issue with more challenges brought on by the lack of no or very scant available qualitative research in finding solutions.

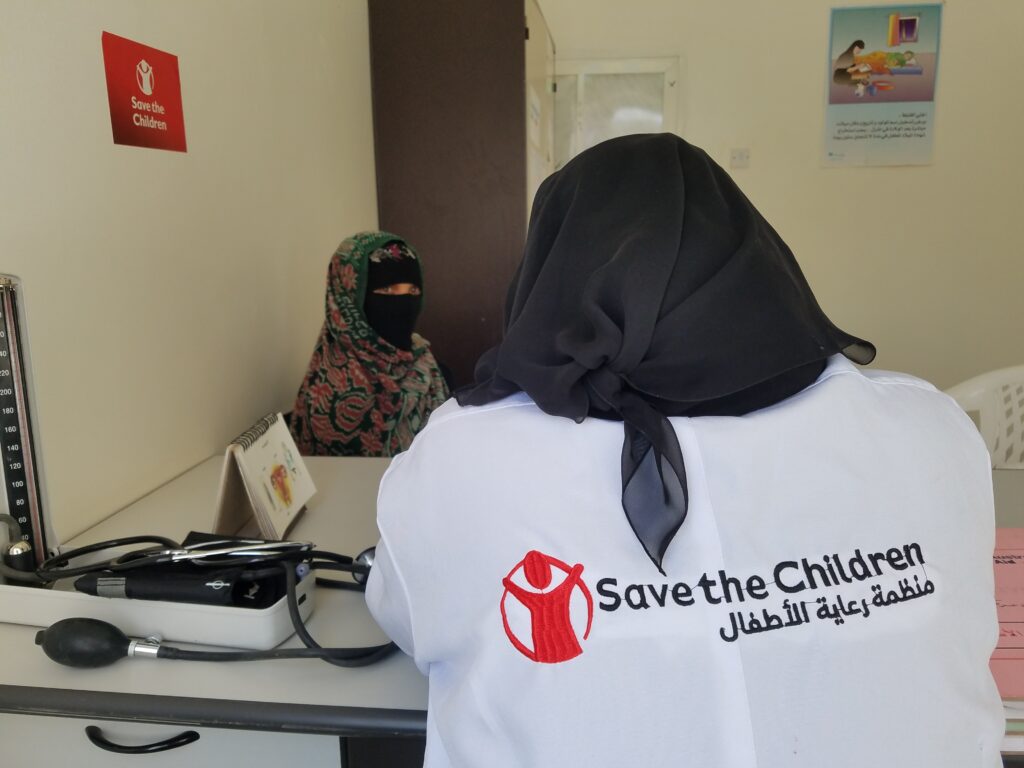

Senior Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Advisor with Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) Lincie Kusters says this lack of evidence led to their and Save the Children International’s Research for Change project, which focused on assessing sexual violence in the context of disaster-prone and conflict-ridden settings. Funded by ECHO, the research was conducted in Borno State Nigeria, and Lahj and Aden Governorate in South Yemen between 2019 and June 2022.

With a particular focus on sexual violence, the project further sought to include references to the full spectrum of SGBV where relevant. It would then provide evidence-informed recommendations to contribute towards increasing the capacity of humanitarian actors, to enable them to adequately identify and respond to the needs and rights of groups affected by sexual violence.

Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) is among the greatest protection and public health challenges to be faced during humanitarian emergencies. It violates the right to life, the right not to be subjected to torture, inhumane or degrading treatment or punishment, the right to equal protection under the law, the right to equality in the family, and the right to physical and mental health (CEDAW 1992).

According to the project research findings, ‘one of the greatest challenges in addressing it in a conflict which involves responding to survivors and bringing perpetrators to justice, is the insufficient or unavailability of data.’ Carried out in Borno State, Nigeria and in Lahj and Aden Governorate, South Yemen, the research shows patterns of sexual violence in humanitarian settings have been influenced by the rise in conflict, mass displacement, and disruption in the rule of law.

GBV Prevalence Rate.

In Borno State, the Boko Haram conflict has brought to the surface gender realities that have seen changes in sexual violence and its incidence. Women have been forced into exchanging sex for food and money, while young girls are forced to accept the fate of forced marriages to ensure their families are protected and fed.

There are 8.5 million people in need of life-saving assistance while 1.7 million of those affected are women of reproductive age. GBV prevalence rate is estimated to be at 30%, and sexual violence is at 16%. While Nigeria has ratified international and regional human rights treaties and policies, their implementation was uneven across the country.’

The economic crisis continues to worsen with numerous outbreaks and changing conflict lines with the number of internally displaced persons standing at over 4 million. Children were the group most frequently mentioned in south Yemen, while rape, especially of children and teenagers, was believed to be the most common form of sexual violence. Male children were mentioned to be more often affected compared to females. Child marriage was thought to be on the increase since the war started, with the youngest age group recalled being nine.

‘If this was happening in other countries … if something like this happened to a child, half the earth would know and would demonstrate… no light has been shed on us… meaning that everything has become normal.’ – Teenage Girl, Lahj.

‘In both contexts,’ Kusters says, ‘There is a lack of data on sexual violence. The study was qualitative and engaged health care providers and humanitarian aid workers, survivors and community members, and assessed the services in health facilities.’ According to her, it was imperative to investigate the perspectives of the survivors, what kind of support they got, and the kind of health service provisions they had.

It was also imperative to investigate how and whether international and national guidelines on dealing with sexual violence in these settings are adhered to. ‘There was the need to identify prevalent types of sexual violence, responses, and the quality of services available. This would give insights to humanitarian aid practitioners in both settings on what kind of sexual violence responses exist and if there was adherence to the guidelines on working with sexual violence in service provision,’ she says.

Results from the research point to the link between conflict and the increased incidence of some forms of violence such as sexual exploitation, early and forced marriage, and marital rape.

‘My father forced me to marry someone. He said that I must marry that man. I told him that I did not like that man, but he said that if you did not marry him, there would be no you and no me…’ A 22-year-old woman in Gwoza IDP camp, Borno, Nigeria.

Such revelations are proof there is a breakdown in the socioeconomic systems, causing sexual exploitation. Sarah Ashraf, a global health expert with Save the Children says in South Yemen, the conflict has led to a breakdown in social structure, economic hardships and cultural norms. This has translated into reduced accountability exacerbated the increase in sexual violence and supports the abuse of power.

Taboo Subject.

While sexual violence incidences are prevalent in both contexts, research shows that their forms differ. What is considered by some as sexual violence, differs from others, as does how people react and speak about it in the two settings. ‘In South Yemen, talking about it is seen as taboo. There was hardly any response from support.’ Ashraf adds, ‘It provides insight to practitioners and governments into the urgent need to prevent sexual violence and provide better support to survivors.’

In Borno state, Nigeria, the landscape is different. Discussions on sexual violence were less of a taboo. The existence of sexual violence was acknowledged. There are forms of sexual violence that are known and talked about such as rape and abduction. However, rape within marriages is not considered as one,’ explains Diana Amanyire, global health expert on SRHR and technical advisor, Save the Children.

‘In the South of Yemen,’ she explains, ‘the conflict and economic crisis are prevalent but sexual violence being used as a weapon of war was not something that came up. It is a phenomenon that is happening, but not so obvious and on such a massive scale that people are okay to talk about it.

‘There is also the problem of very few things being done or certified within the health system for sexual violence. Some actions are being taken, but these are adhering to the formal protocols, so space to talk about it openly is still limited.’

In Nigeria, Amanyire states, ‘There has been a lot of sensitization about SGBV on the ground level through community initiatives such as aunties (older women in the communities). The local leaders have also created a conducive environment for victims to know that they can speak up.’

These structures, she says, have built a level of trust that is providing a beneficial platform in Borno State for victims to speak up. They are a model example of how community-based initiatives can be beneficial to victims in these settings, even with a lack of humanitarian aid, or where it has been withdrawn or is reduced.

The project reveals challenges that need to be acknowledged in the wake of sexual violence in humanitarian settings such as survivor naming and shaming, and self-stigmatization, which means few survivors ever speak out. A lack of accountability also means perpetrators stay unpunished and there is hardly a legal support system.

Utilizing the Research.

The question remains, how will this research be turned into concrete action situations in these settings? According to Kusters, the next step is widely disseminating the findings so they can be used by different stakeholders and incorporated into programmes. ‘One significant aspect of conducting the research was to provide insight to service providers, government agencies, NGOs and humanitarian aid agencies to make a difference. We engaged MOH international and local NGOs.

‘After the research, we had validation sessions with key stakeholders, through dissemination sessions in different countries, and organized webinars. We will continue this engagement so they can incorporate research findings into their programmes. Currently, the focus is on disseminating and advocating for improved services,’ she says. One major platform that will be used for dissemination is Share-Net International’s digital platform which has a member base of over a thousand practitioners and policymakers.

Ashraf says in Yemen, they are already finding ways to turn the research recommendations into action. ‘The response from the MOH was very promising. They organized a workshop with different stakeholders and began developing an action plan. This was to see how the results can be used and what can be done in the immediate and long term. This was to ensure that the health system incorporates some of the recommendations.’

‘In Nigeria,’ Amanyire says, ‘Research findings have been disseminated through the GBV subsector in the health ministry and implementing partners. There is commitment at the Civil Society Organizations (CSO) level. We are engaging with implementers, so they can find ways to incorporate some of the recommendations into their programming. However, the subsector needs to be engaged to come up with concrete plans.’

Additionally, simple recommendations that do not require humanitarian assistance should be lifted. Ashraf explains: ‘One of the main objectives of the research was to try and come up with concrete suggestions and guidelines enabling the health system to be improved and provide better services of a quality that are acceptable to the communities.

‘Those who do not require funding should be given support to make those adjustments and changes to the health system. That is the easier route. There are aspects of the health system that will require funding no doubt. However, some need policy changes, guidance, aligning and realigning protocols with international standards which is a big aspect of this study.’

The above, she says, can be done through existing forums such as the health cluster forum, the reproductive health sub-working forum, and the GBV working groups. They can play a significant role in endorsing some of these actions as well as holding stakeholders and partners accountable. They also keep dialogue and discussion open.

According to Ashraf, a sustainable humanitarian support model can be achieved by reconciling services and finding ways to deal with the breakdown of the social and economic system. ‘When livelihoods are affected, there is an increase in vulnerability. All stakeholders should be engaged to create a multisector approach from prevention to sustainability; psychosocial services, social services, protection-related services, legal aspects and Food Security and Livelihood (FSL).’

Amanyire adds that equipping women-headed families and vulnerable groups with income-generating skills is key in ensuring that they have income sources in cases where they do not have access to distributed rations. ‘In Nigeria, there is proof that there have been developments in this, but it was still not strong enough to give them that economic power to feel like they are in a safe space to say no to exploitation. This needs to be strengthened right from the start of humanitarian responses and built into the system.’

‘As we focus on sexual violence,’ Ashraf says, ‘We need to ensure we design holistic comprehensive projects right from the beginning and not look at it from a health perspective or a psychosocial perspective and then link it up with others. That linking up aspect becomes more challenging if it is not part of the same project.’

Focus on Boys and Men.

‘There is a need to change strategies and relook at how we programme for SGBV in different programmes differently so that all can access services. This research brought about a lot of positive attention to the topic and subject area and that is what was needed.’ Ashraf and Amanyire emphasize the importance of using the research to implement and create projects supporting country programmes to turn these findings into actual tangible interventions.

Share-Net International is the leading knowledge and connections platform on SRHR. It has a network of experts and member organizations who combine the strengths of key international actors while harnessing localized knowledge. This promotes the development of better policies and practices in SRHR, including HIV.

‘We use the Share-Net knowledge platform to advance the Sexual Reproductive Health agenda, especially those topics and themes that are less addressed or known such as SGBV in humanitarian settings,’ Dorine Thomissen, Share-Net International Coordinator says.

She says they bring together researchers, policymakers and practitioners with the aim of improving policy and practice. ‘We want the results to be accessible to a wider public that will use them for improvement of programmes. It is not only policy and practice that we aim to improve through this research, but also relevant issues that come up.’

‘The way SGBV is discussed around the world has changed, but this research project is very specific. That is why as part of our objectives we will provide the opportunity for it to gain more attention. This is so that recommendations can be turned into policies and actions.’

She is confident that dissemination of the research project on their platform will be of substantial benefit. Drawing from examples given by members of Share-Net, she says there have been positive responses. This shows that research disseminated on the platform is being used for change by members through integration into their programmes or for lobbying and advocacy purposes.

Leave a Reply