The story of Benin’s toll-free number

Cases of violence and harassment in the workplace are still very prevalent and appear to be intensifying. Sadly, its victims choose to remain silent out of fear of retribution from their harassers and victimisers. To counter this, the Centre d’écoute et d’Accompagnement CAPJ/COSI-Benin offers a free helpline for women in Benin who are victims of violence and harassment in the workplace.

Text: Elizabeth Kameo

With a slight smile on her face, 41-year-old Françoise (not her real name) says, ‘to overcome, you have to confront. I had to face and overcome the challenges, for my children and me. After suffering in silence for years I had to find help. That is how I came to the psycho-socio and legal support centre, CAPJ —Centre d’Accompagnement Psycho-social et Juridique. Today I am a survivor.’

In March of 2007, 26-year-old Françoise began working as the executive secretary to the director for a private transit and transport company in Benin. Three years later her boss, the owner of the company, began sexually abusing her. It is estimated that workplace sexual harassment makes up twenty percent of gender-based violence cases in the country.

‘One day he called the office from his house and asked me to get him some paperwork. On getting there, I found him alone and that is when he sexually abused me. It was the first time and would continue for over nine years. He threatened me saying if I ever told anyone, something bad would happen to me, so I kept silent.’

From then on, she says he would send other workers off on errands, ensure it was just the two of them left, and subject her to more sexual abuse. The first attack took place in October 2010 and lasted until the end of November 2019. ‘When the person you respect the most abuses you, you lose something. For me, it was my courage and confidence. I had no support system at the time, so depression set in since I was always worried about losing my job. I was suffering in silence until I met my partner.’

In February 2021, two years after the abuse had ended, she finally found the courage to confide in her partner and resign from her job. She sought help after a friend told her of CAPJ, though it was not until August this year that she went there. Today, her case file is with the Vice Squad. ‘At the centre, I was listened to, offered psychological help, and provided with a lawyer. It has been recomforting. I feel protected and supported.’

‘The next step is the court hearing,’ Marilyne Sourou, Head of the Psycho-socio and legal support Centre says. ‘In the meantime, we are waiting to have a meeting with the lawyer that COSI-Benin has hired for her.’ CAPJ is part of COSI-Benin —La Confédération des organisations syndicales indépendantes du Bénin. It was set up by the latter with support from its Dutch partner organisation, CNV Internationaal, on the realisation that there is a growing number of women and girls who are falling victim to workplace harassment.

It acts as a listening and reconciliation centre, offering legal services in situations of conflict in the workplace. Located in Cotonou, it provides a place for victims of violence and harassment in the workplace and learning environments who are listened to, advised, and guided psychologically, legally, and given health care where necessary.

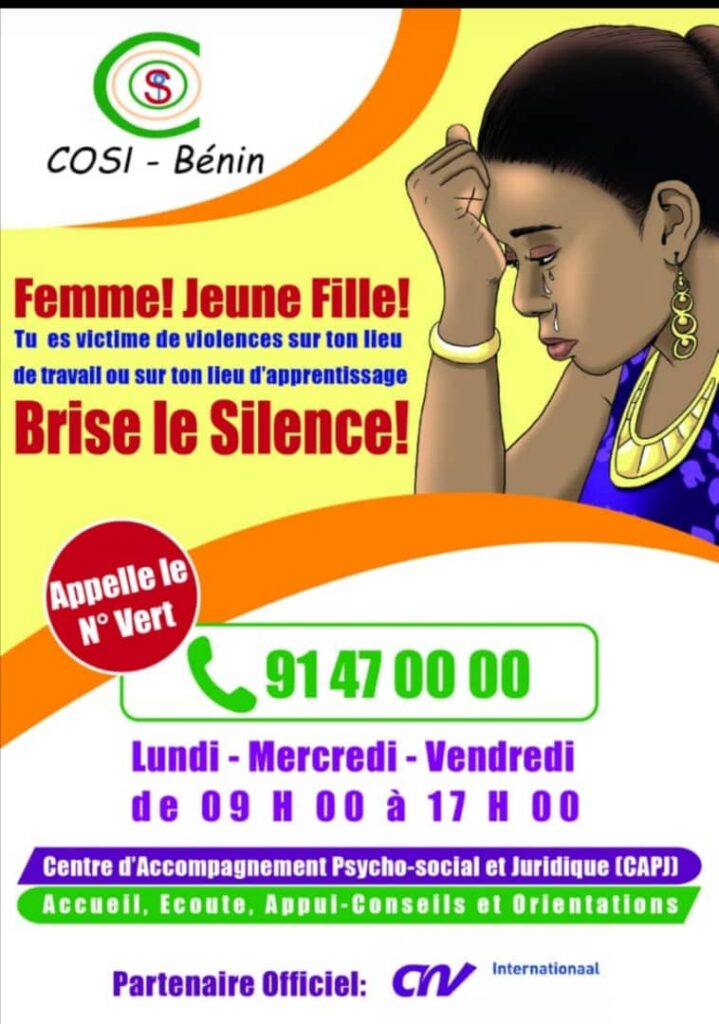

Survivors throughout Benin can reach the centre by calling the toll-free number 91 47 00 00. It is the only helpline in the country set up with the sole purpose of helping survivors of workplace harassment. ‘It is available free of charge for subscribers of the most popular mobile operators in Benin. Through it, the CAPJ registers complaints and refers victims and survivors according to their geographical location,’ Sourou says.

Using the helpline, they hope to break the silence as far as sexual harassment toward women and girls in the workplace is concerned. While Benin has a legal framework for the prevention and repression of gender-based violence as stated by Law 2011-26 of 9 January, as in many other African countries, these laws are only good on paper.

‘Lack of respect for women’s rights is still the norm. They still have no access or find difficulties when seeking justice in cases of violence. There is a weak, or in most cases no implementation at all of the laws adopted in favour of women,’ she explains. One of COSI-Benin’s tasks is advocating for the ratification of ILO Convention C190 to condemn all forms of violence in the workplace, including sexual harassment.

In Benin, 69 percent of women and girls are reported to have been victims of different forms of GBV —physical, verbal and psychological, sexual, and harmful traditional practices. Twenty percent of these are cases of economic violence. A trade union organisation, COSI-Benin also set up a National Women’s Commission whose aim is to combat workplace sexual harassment by informing and sensitising about their rights as well as the country’s legal framework.

Today Françoise is one of those the centre has helped find answers and seek justice. She no longer considers herself a victim, but a survivor. ‘There was a time in my life when I considered committing suicide, but then I realised it was not the way out. With three children, I sought help from COSI-Benin. I now have support from the centre, but I hope to gain support from the judicial institutions as I seek justice to have my abuser held accountable for his actions,’ she adds.

‘My abuser nearly destroyed my life and that of my children. They did not go to school for a year because I could not afford it.’ As for the long-term effects of abuse over such a long period, she says there could not be a bigger challenge. ‘I hope to find justice and see my abuser punished for his crime. I am still jobless and depend on my partner and family for my financial needs. I cannot imagine going back to work with a male boss. Maybe one day, but not yet.

‘Those in power need to understand what is happening, listen, and support us. When you are abused, you become vulnerable and need all the support you can get. I have confidence in the system and I hope my abuser will be judged accordingly.’ Since 2020 to date, the CAPJ has registered 157 complaints including sexual harassment (mainly in domestic workplaces), sexual assault, physical violence, and threats; all at the workplace.

They currently have two pending court cases. Legal services are provided free of charge to survivors and victims through a partnership with a lawyer’s office whose costs are covered by COSI-Benin with the support of CNV Internationaal. ‘This was put in place after we realised that most women found difficulties in obtaining justice because they could not afford legal fees,’ Sourou says.

She explains that as per the centre’s role of listening, when survivors reach out for help they are received in confidence, listened to, and their complaints registered. ‘The centre then advises and informs, emergency measures are taken where necessary, and the person in question is informed of the legal system and their rights. We discuss available measures that can be taken and orient them towards the most suitable service, legal, psychologic or other,’ she states.

While the CAPJ is not in a position to offer holistic care to survivors, she reveals that they have an alliance with Social Promotion Centers —specialised institutions of the State with the necessary resources to help victims and survivors. But even with the toll-free line in place, she admits there is still a lot of ground to be covered to ensure that its services are accessible to workers all over the country. To this effect, CAPJ has organised awareness and sensitisation workshops in the south and north of Benin, and public outreach programmes through radio and television broadcasts.

They are also tapping into the power of social media. ‘A WhatsApp forum was created in January 2021. It is a melting point of information and awareness called ‘VBG, On en parle’ (Let’s talk about GBV). It brings together media professionals, anti-gender-based violence activists, lawyers, opinion leaders, and trade union leaders. With about 200 members, the forum holds debates on topics related to violence at work and on Convention 190 and Recommendation 206 adopted by the ILO on violence and harassment at the workplace.’

The biggest challenge, Sourou contends, is “Breaking the silence.” ‘Our cultural context does not favour this; it is really difficult for victims of violence to speak out in their workplace. Beyond culture, they are afraid of finding themselves unemployed, or not being sufficiently protected from their tormentors. Since the legal process is also long and tedious, they do not always have the resilience and strength to deal with it. In addition, currently CAPJ is not known and accessible to all and we still lack technical resources.’ But this is not stopping them from fighting the good fight.

She is confident that Benin’s current government is on the right track to tackling GBV in the workplace. She also believes the country’s ratification of Convention 190 and Recommendation 206 will be useful in this quest. But adds; ‘most importantly women who languish under the weight of silence need to break it and free themselves.’

Helplines play a vital role in allowing people who may be in distress or in need of psycho-social support to communicate in their way and in their own time. The fact that it is confidential gives people a sense of control, making them feel free to discuss matters far too risky to share face-to-face. Calling a helpline is a great way to be heard and to get sound advice on how to approach your problems.

When the person you respect the most abuses you, you lose something. For me, it was my courage and confidence.Lack of respect for women’s rights is still the norm. They still have no access or find difficulties when seeking justice in cases of violence.

In Benin, 69 percent of women and girls are reported to have been victims of different forms of GBV.

Leave a Reply