Turning Waste to Wealth; One man’s trash is another man’s treasure is a phrase that Erick Lovoga and his friends took to heart. They managed to form a consortium that offers a multi-thronged attack on climate change, unemployment, high cost of living and environmental cleanup. At Kariobangi Community Kitchen, people not only cook their meals together, they also get a chance to share ideas.

Kariobangi is a settlement eleven kilometers East of Nairobi’s City Centre. It is home to the famous Light Industries, where entrepreneurs own and run several cottage industries. Most of its youth have ventured into diverse income generating activities, evidenced by the large number of soccer players, performing artists and acrobats who have represented the country at national and international platforms. Erick Lovoga, together with his team, represent this demographic. They have been operating Kariobangi Community Kitchen which recycles waste to fuel.

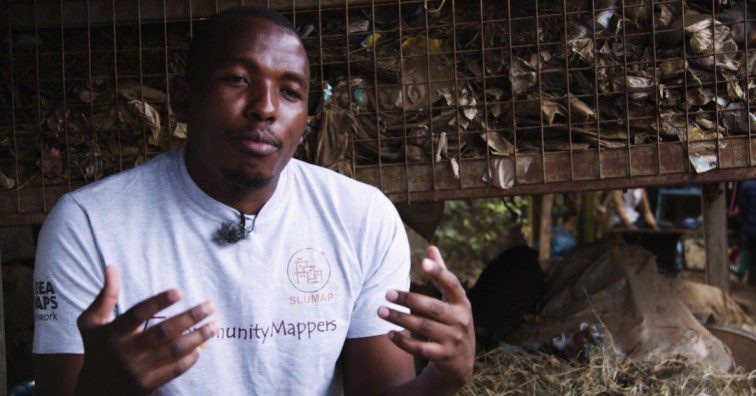

About Erick

Born in Sabatia in the former Western Province of Kenya, 36 year old Erick doesn’t remember much about his early childhood. “My mother and aunts tell me I was a very active and curious child. One of my aunts never misses a chance to tease me, by reminding me that I was plump and short back then. To help me shade off some of the weight, my mother would take me with her to fetch water from the community watering point, which was approximately three kilometers away,” he says. He doesn’t have much recollection of his early childhood, though he recalls moving from one school to another as they frequently relocated, till he found himself in Kariobangi.

Environment and Waste

Waste management is an income generating venture that youth in Nairobi have engaged in since the defunct Nairobi City Council allowed community based organizations to assist in cleaning and managing waste at the community level. In the year 2000, organized and registered youth self-help groups from Kariobangi were allowed to collect waste from households at a fee. Through their representatives, they entered into a binding agreement with households and plot owners on how much, when and how the fee would be collected. It’s these funds that they used to purchase liner bags, litter bins, and other protective gears that they use in the course of their operations. Waste collection is a lucrative venture that favors the bigger and well equipped enterprises that get county tenders and which operate in the leafy suburbs. Most youth groups are still ill equipped, hence they never get to win such tenders.

In 2006, Erick and a few of his friends decided to form and register a youth group that would take advantage of the available opportunities in waste management. This was necessitated by the frequent arrests of youths by the police, who accused them of being idle and loitering with intent to commit crime. “We were able to register a self-help group comprising of membership from both genders,” he says.

The group, with support from the local administration, managed to organize community cleanup activities. They managed to create a good network within the locale, collecting the waste at a modest monthly fee of one hundred shillings per household.

The Post-Election Violence

“During and after the 2007-2008 post-election violence, waste management was one of the initiatives that was negatively affected. Kariobangi was one of the hotspots where youths were actively used to destabilize the community. Operatives from the opposing sides mobilized youths to defend their party and business interests that were being targeted during the chaos. As the chaos persisted our group, just like many others, was affected. Some members had a hard time accessing certain households because of their ethnicity. This meant that group members couldn’t make money, a scenario that led to a lot of them being idle.

“To mitigate this, we called an emergency meeting of all groups that were dealing in waste collection and environment management in the area. After deliberating on all possible ways to resolve the challenge we were facing, and which was having a negative impact on not only our members but the entire community as well, we resolved to form an alliance. This move was beneficial to our course because it allowed our operations to continue regardless of our tribes.

“In 2009 during reconciliation efforts led by the government and non-government organizations, our efforts to merge the groups was highlighted as one of the ways a section of the community had employed to build and foster peace amongst warring communities. Formation of the alliance gave us a voice and negotiating power. In September of the same year, we formalized the registration of Kariobangi Waste Management Alliance (KWMA) as a consortium of waste management groups operating in the area,” he says.

“In 2010 KWMA was a beneficiary of the Community Driven Development Project that was being implemented by the Global Peace Foundation, which itself was very instrumental in organizing initiatives to foster peace and harmony in Kariobangi. It was through this project that we managed to stay intact as a team through their capacity building meetings, for peace was very important at that particular period. Our revenues from waste management also improved,” he says.

In the course of their work Erick and his team started promoting recycling from the household level by giving three polythene bags, for plastics, biodegradable and non-biodegradable waste respectively. If they found you had sorted your waste correctly, you would be charged less than the usual amount.

Birth of Community Jiko

In 2013, KWMA gained more visibility for their involvement in environmental activities. They managed to partner with the Africa Conference on Volunteer Action for Peace and Development (ACVAPAD), a consortium of some of the biggest corporates in Kenya.

“The goal of the partnership was to support environment conservation, youth empowerment and employment efforts that KWMA and World Vision were involved in. It is during this time that Dr. Manu Chandaria, who was the patron of the consortium, challenged us to come up with innovative ideas of managing solid waste that was becoming an eyesore not only in our area, but across the city.

“The Community Kitchen idea was informed by the fact that most of the households in Kariobangi had complained of life being unbearable as fuel had become too expensive. Many had resorted to using charcoal and firewood, which reverses the efforts made by environmentalists in conserving our forests and combating activities that contribute to climate change. We wanted to provide our community with cheap and readily available cooking energy, as well as provide a centre where community members could meet, engage, and share ideas, thus fostering peace and cohesion within our diversity. The idea received support and funding from the KCB Foundation, Safaricom Foundation, Chandaria Foundation and World Vision, after it was subjected to a business plan writing and presentation competition.

“I was tasked with the responsibility of drafting the concept, presenting and defending it in front of a panel of established and successful corporate CEOs in the country. Our plan was successful and we were able to get a 3.9 million-shilling funding for our idea. The Kitchen was to use pure waste for cooking. The team would collect waste from the households, bring it to the site, and dry it in direct sunlight. Sorting would then be done to separate the toxic and explosive waste from the ones that can be safely burned.

“Before embarking on setting it up, a lot of time and resources were invested to put in place a proper method of handling all the waste materials required to power the Jiko without negatively impacting the environment. All waste used at the kitchen is carefully sorted and dried before being used. The Jiko uses pure waste, with its chimney designed in a way that makes it impossible for it to emit harmful or toxic matter to the environment. It can cook up to six different types of meals once it is fitted with six pallets.

“The Community Jiko idea and design requires a big space to set up. The objective is for the community members, regardless of their tribe or creed, to be able to meet at a central place, cook and share ideas. We believe, and it is evident, that this has helped reduce the amount of solid waste in the community. Households have been able to save on the money they would have spent on fuel, as well as reduced intergeneration and tribal strife. The Community Jiko concept and project has been replicated in other regions and communities after its success here.

“The consortium that supported the Kariobangi project has been able to set up similar ones in Mathare, Kibra, Kawangware, Roysambu, and Dagoretti. As people who pride themselves in managing waste and conserving the environment, we support all efforts that advocate for the promotion and protection of our environment, for the current and future generation. If you invest in the environment today, you will get high and unmatched rewards in the future,” he concludes.

What you call waste in your house is someone else’s wealth in form of fuel therefore, keep it nicely.

Leave a Reply